Ambiguity, Within Reason: Walter Serner’s Continuing Critical Relevance

Alicia Gladston looks at the works of Walter Serner and how he used satire and absurdity to undermine rigid fascistic categorisations of the self via the state during the 1920s and 1930s. She in turn argues for a continuing embrace of ambiguity of both our individual identities and creative processes as a response to present day authoritarianism.

Ambiguity and contradictions are immanent to all our identities and relationships, along with the challenges of expressing ourselves through language given the potential for misinterpretations arising from differing sociocultural norms. And yet, there is a continual reinforcement of categorical certainty today as part of political, social and cultural discourses in the face of unsettling global outcomes brought about by globalisation, world economic/ecological crises and the COVID pandemic. What can still be celebrated in ambiguity as an arguably inescapable aspect of human existence; its continual dismantling (deconstruction) of relational categorisations and revealing of diverse significances between us.

In his book Being a Character - Psychoanalysis and Self Experience: Fascist State of Mind (1992) Christopher Bollas writes, “to achieve totality, the mind (or group) can entertain no doubt. Uncertainty, doubt, self-interrogation are equivalent to weakness and should be expelled from the mind to maintain ideological certainty.” Bollas writes about Germany’s Nazi state during World War II and the power of political ideology to influence society to the point that no alternative way to be or think feels possible.

For Bollas, the essence of the fascist state of mind was the presence of ideology in everyday life that stifled the ability of individuals to disagree or learn by “claiming to possess secret truths that explain all phenomena.” Inherent to which is a paradox that by creating parameters and categorising a person, it sets them free.

How does culture lead us towards categorisation of that sort? Throughout history within various philosophical/theological traditions - including those of the so-called ‘west’ and ‘east’ - the gaining of insight into perfect reason and creativity has been exercised through various forms of metaphysical speculation. Western notions of complete understanding reside in a ‘Logos’ (word of God) focused philosophy rooted in classical Greek and Christian theology. European/American post-Enlightenment philosophy continues to uphold the traces of such thinking –albeit in supposedly secular-scientific discourses– including those of politics and psychoanalysis. The Western discursive tradition raises up age-old binaries that oppose irrationality and ambiguity (untruths) using (Apollonian) rationality and reason (truth), viewing the former as a (Dionysian) threat to order that must be excluded and, if possible, extinguished.

Set within that discursive context, psychoanalysis seeks to identify and ex/dispel madness as a means of restoring reason.

Psychology was nurtured in the tradition of the logos - the word psychology is in fact a combination of psyche and logos, meaning “knowledge of the soul”. Psychoanalysis was initiated under the influence of psychology by, among others, Sigmund Freud who, in the late 1800s, began to develop ways of analysing the human unconscious and its suppression of traumatic memories, through methods such as the interpretation of dreams and attention to stream of consciousness (the talking cure). Freud’s approach to clinical psychoanalysis resides on the idea of a hierarchical framework that differentiates between the categories of the readily observable conscious and the hidden unconscious as well as the id (uncontrolled desires), and the (socially controlling) ego and the superego. Within this model the unconscious and its companion the id are cast negatively as ambiguous and irrational in relation to the conscious and the egos – and, thereby, the idea of the logos upheld.

Psychoanalytic categorisation is signally undermined by way of textual manipulation and bewilderment in Austrian author and co-founder of Dada, Walter Serner’s texts Last Loosening (1920) and The Handbook of Practices (1927). Serner demonstrates that total denial of the irrational self at the will of the state leads to repression, denial, and outright fascism. Serner challenges the ‘authenticity’ of categorisation by celebrating the ambiguous and de-familiarising. Writing at a time of rising nationalism and authoritarianism he laughs in the face of strict formalities of being and witnessing, writing to undermine, in a bid to survive. As Serner observes, "The world wants to be deceived, and is truly malevolent when you do not oblige."

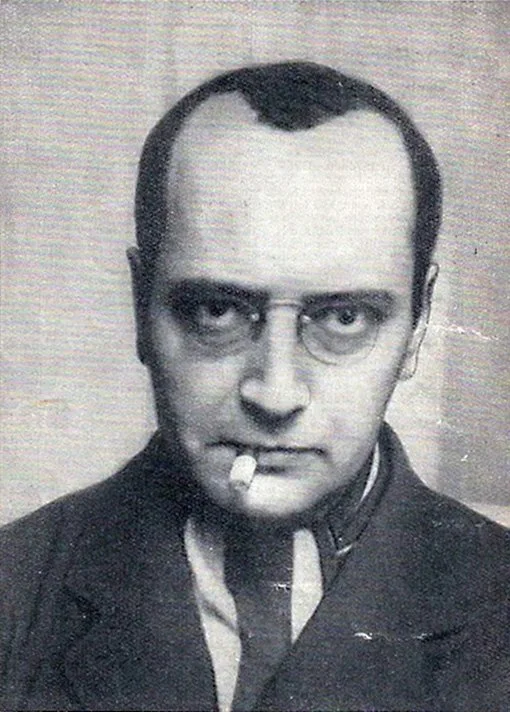

Walter Serner (1899-1942) was born into a Jewish family in the Bohemian spa town of Karlovy-Vary in what came to be known as Czechoslovakia. While studying law in Vienna, he wrote for art magazines and anarchist papers, and, as The First World War broke out, conscientiously objected by fleeing to Switzerland, coincidentally meeting the Dadaists to-be. Serner fertilised Dada with his ideas then destroyed it, abandoning the project altogether after regarding them as “careerists caged in their intellect”. Gleaned from a description of Serner by the Dadaists, we witness him as “the great cynic of the movement, the total anarchist, an Archimedes who put the world out of whack and then left it to hang." Sener’s general ethos was attacking the bastions of Western culture: psychology, religion, philosophy, and institutions. As such he was the embodiment of a pernicious critique of rational categorisation within and beyond Dadaism.

In his two-part book Last Loosening: The Handbook of Practices, Serner contemplates the illusions of sincere conduct and authenticity in public life with philosophical and ironic tact. In doing so, he urges the reader to become a successful ‘Conman’ in response to society’s illusions; to evade any strict sense of identity, manipulate situations and behavioural rules within prevailing ideologies, and finally uphold boredom as the root of most (deconstructive) habits.

The handbook, while being satirical, is serious minded. It was written during the rise of political authoritarianism in Europe and the popularisation of psychoanalysis during the 1920s and 1930s, making fun of both with brattish disregard. It was also a salty goodbye to the art world, as member of the Dadaist scene Hans Richter confided, "Serner was so naïve as to think he could find sympathisers in the world of art. After turning his back on the art world — that would later use his ideas like a brand of laundry detergent — he glorified a world of swindlers in which everyone is engaged in deception."

Serner was publicly antagonistic to the growing right-wing politics of the times. Staying true to his prankish style of playing a conman in real life he started to make local police believe he was indeed a terrorist to the state. This led to Serner living at 34 addresses across Europe between 1915-33 to evade scrutiny, finally settling with his wife Dorothea Hertz, of Jewish descent, in Prague. When the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia in 1939, their attempts at getting a visa to Shanghai failed. On 10 August 1942 Serner and Hertz were interned in Theresienstadt concentration camp before being sent north on a train to Riga, shot in the Bikernieki forest in Latvia and then buried in a mass grave.

Last Loosening is both survivalist and ironic. Ironic in that it seeks to expose the facetiousness of social interactions and the inability of the bourgeoisie class to shake off its self-importance; survivalist in the sense that living as a Jewish man with antifascist sentiments would never be safe. There was no other choice but to protect the nuanced self, to teach evasion from profiling and capture. Serner’s rule no. 420 in the Handbook of Practices states, ‘Give everyone the impression that you find women unbearable, have no children, and accept the prevailing discourse.”[1]

Writing in his book Cool Conduct (2002) Helmut Lethen describes Dada as “a laboratory of indifference to the practice of shaming and disgrace. They set out to make themselves immune to power”. If we can identify anything Serner influenced within the Dadaist project, this attitude was it.

In Dada, everything was a strategy of disentanglement, meaning nothing would be attached to you and thereby shame you.

While this strategy can be freeing and give space for productive disinterest, the peril is a lack of intimacy with others. The Conman instils isolation between himself and the social world by wearing a mask.

Authenticity becomes a practised disguise, blurring the lines between the ambiguous self and the conception of ‘genuine self’ – to the Conman everything becomes impression management.

Codes of personal conduct are manufactured to be familiarising, ordered, and charismatically truthful while the negative space of such masks hide the private personal horror of the erosion of self once we live inside appearances. Serner’s Handbook rule no. 418 asserts, “If all sorts of rumours start swirling about you, deny all the damaging ones over and over, but half-heartedly. The flattering ones only occasionally, but emphatically.”

Other Dadaists also understood language to be a masquerade. They were disgusted by the propaganda and literature that had convinced many innocent people to die fighting in World War I. Language and ideology became nefarious, in their complicity with the insidious war machine. The only means of destroying the mainstream’s ‘Logos’ was to expose its shortcomings and contradictions. Serner achieves this derailment by establishing an ambiguous tone with absurd lines like, “every word is blancmange” (a milk based dessert). If every word is blancmange, then ambiguity is always present, jokingly subscribing words within interpretation to nonsense. Handbook rule no. 298: “The last seven fragments should not only demonstrate to you the meaning of experience (in contrast to stupid psychology) but also persuade you to make note of your own experiences. To each his own handbook.”

The decades between World War I and II were not only a time of hedonism after the horrors of conflict but also interrogation of post-war sovereignty and the interior self. The right wing in Germany sought to develop an authoritarian vision of culture, society and politics during this time, reflected by slogans and oaths such as “behind enemy forces, the Jews” and “the Reich will never be destroyed if you are united and loyal” in addition to the use of icons such as the swastika. Despite fascism's attempts at sterilising transgressional thinking, the mind remained complex. Serner’s codes of conduct abide by fascist ideology’s performative strictness as a self-protective camouflage, coyly resisting the unveiling of the Conman’s identity. Shame culture polices habits, relations and behaviour - as the object of shame culture the Conman exploits this gaze for his own gain yet remains anxious because of it, never free from the surveillance. But how does one familiarise the other without generalisation? Are there parameters to what a person can be, parameters that generalise at the risk of our sense of personhood? How can we be certain of our convictions?

Serner’s masquerading critique of conventional society and culture enfolds an uncertain vision of psychoanalysis as both a remedy and a poison.

Psychoanalysis has the pressure/burden of being the supposedly authoritative imparter of reality and truth – of what is rational and sane in opposition to what is irrational and insane.

Analysis holds out the possibility of a cure for irrationality (a return to the logos) dependent on a rationalising and hierarchical distinction between the two. This distinction supposedly provides the basis for insightful and effective treatment. However, many differing external factors and interpretative points of views in curative interpretations (talking cure) given by doctors (analyst) to patients (analysand) cut across that distinction by acting as pharmakon. In his essay ‘Plato’s Pharmacy’ Jacques Derrida employs the Greek term pharmakon – a word signifying by turns ‘remedy’, ‘poison’ or ‘scapegoat’ – to highlight the ways in which language productively derails authoritative meaning. The irrational and ambiguous are not just the subject of psychoanalysis, they remain indivisible from its processes. The rationalising binarism of the logos is continually poisoned by the uncertainty of the psychoanalytic dialogue. Neither reason nor irrationality is ever eliminated but held in a persistent, uncertain dialogue.

Nazism retained psychoanalysis (withstanding despite its semitic associations) as a useful handmaiden to ideology, asserting that the mental distress of “Aryans who had neurotic conflicts” could be corrected ''given the proper guidance of an innate German will.'' Nazism pressured therapists to ''heal'' in a way that could ''subordinate the individual to the community'', thus abusing authoritative power and using the categorical binary positions of psychoanalysis to impress their will on suffering subjects; many of whom were made ill by the life that the Nazi’s had imposed upon them as they suffered an imposed silence over what they bear witness to. This included attempts to ‘unhomosexualize’ individuals; the further remedy to which was deportation to death camps where poison gas was widely used to despatch undesirables. Poison gas translates into German as ‘giftgas’. The prefix ‘gift’ in German signifies both a present or gift and a poison. Yet another instance of the pharmakon in action in relation to psychoanalysis.

Serner’s response to the dilemmas posed in the context of authoritarian rationalism can be found in Handbook rule no. 52: “Philogistic crapule: wanting to have no system is the same as a new one. Truth (la blague) cannot even become a problem if it must be a linguistically acceptable premise. Every person has always believed in too much: you don’t have to buy into anything at all. It is here, however, that the private individual is cognizant that one cannot decide but only - suss out which of the two poles the thought seems to be moving closer.” Here, Serner asserts not that one should simply choose one system over another – such choosing relies ultimately, as he sees it, on the rationalising binarism of the logos. Rather, it is not to choose at all. Serner embodies and amplifies Dada’s commitment to undermining the Logos and making the self undefinable. It is only when external forces attempt to define an identity or authenticity that the self is forced to be stripped of its ambiguity. A stance sustained also by Derrida and other adherents of deconstructionism.

Despite the interventions on rationalising authority by Serner and related Dadaistic and quasi-Dadaistic cultural movements before and after World War II, including theory developments like deconstructionism existing as a successful foil to philosophical rationality, there are still controlling states and ideologies that seek to dispossess individuals of their ambiguities today. Indeed, within nation states such ideologies have been accentuated by the impact of post-Cold War globalisation, re-creating binaries that seek to divide and cause friction in their efforts to attain power. Intensifying communications between societies and cultures via technology, and the acceleration of globalisation and its economic benefits has emboldened authoritarian ideologies world-wide that vehemently object to the ambiguities witnessed by Serner. These advancements have become a deconstructive pharmakon of a sort themselves, providing the luxury of instant connection, cheap products, self therapization and entertainment ‘remedying’ life’s inconveniences at to degrees existentially ‘poisonous’ costs.

In logos, rationality finds connections between categorical subjects to establish truth; however it is always in binary opposition with the irrational (ambiguity) to establish a final resolve, historically on its own terms. Approaching this bid to oppress and stifle by dismantling binaries, language and relational categories we can reveal the depth of life’s significance to each other and ourselves. Walter Serner’s creative life is a lesson to be wary of stripping ourselves of ambiguous depths, and to be wary of the people, institutions, religions and politicians that try to tell us who we are, and that retaining a sense of humour is vital to not becoming destroyed by such forces. Handbook rule number 55 “You’re greatest advantage? Not being what you seem; indeed, not even seeming to want to be what you are not.”[1]

[1] All quotes titled ‘Handbook rule” taken from Walter Serner’s Last Loosening

Alicia Gladstone is a writer and costume maker living in London.