Rays of Relation: Maggie Nelson in Conversation

MAGGIE NELSON

Caitlin McLoughlin talks to the author of The Argonauts and On Freedom about her new book Like Love, the complexities and misinterpretations of shame and taking risks.

INTERVIEW BY CAITLIN MCLOUGHLIN

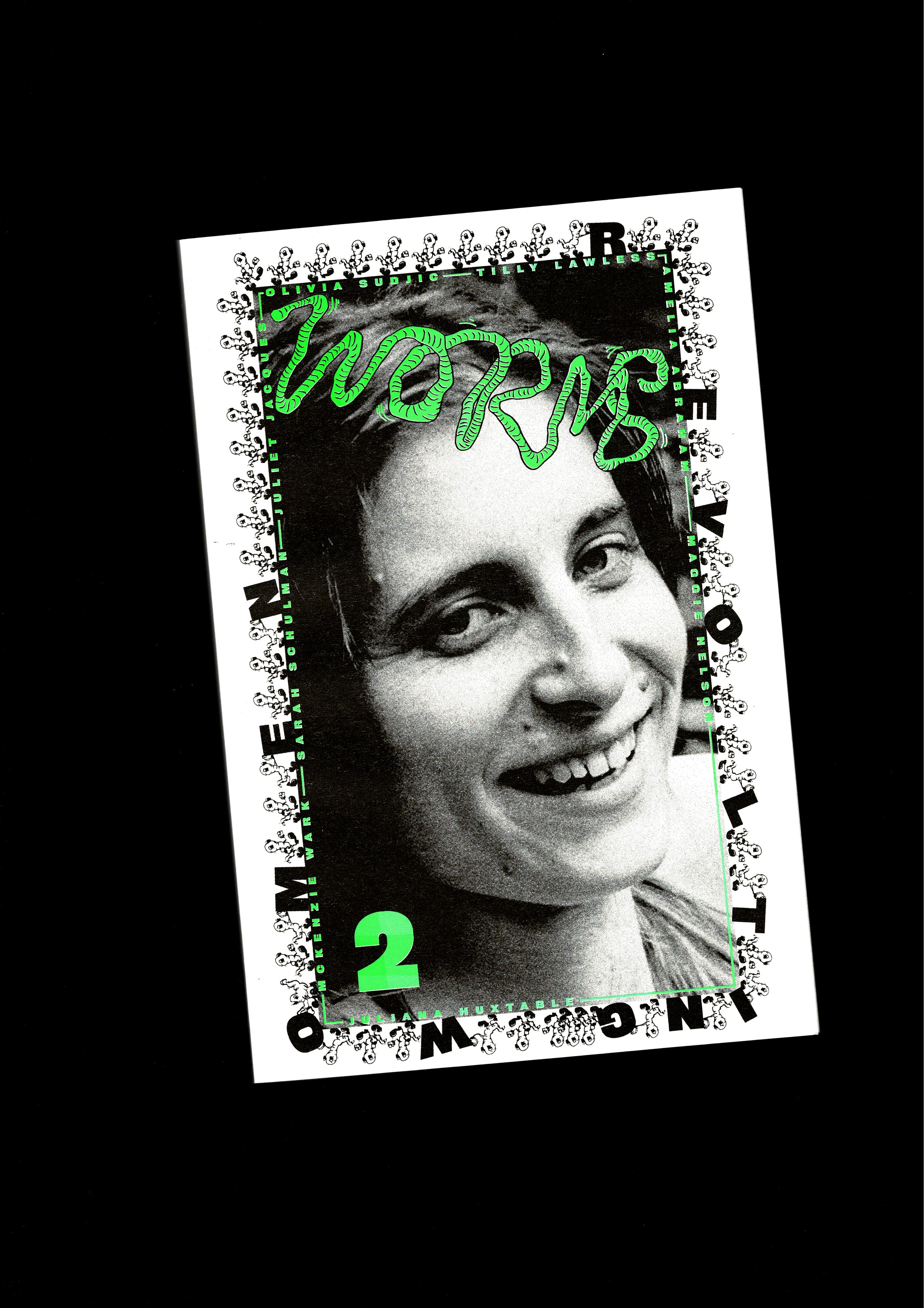

SELFIE BY MAGGIE NELSON

The image of the knot recurs often in Maggie Nelson’s writing. It’s fitting, as her work deals in complexity, inhabiting the overlaps and interstices between art, literature, theory and the multiplicities of how we live. One such knot is the initially unassuming notion of freedom, which, as she begins to unravel in her 2022 book On Freedom: Four Songs of Care and Constraint, is anything but. Through the lenses of art, sex, drugs and climate, Nelson grapples with the often contradictory, unsteady versions of freedom in the venn diagram of where they intersect – “It is here that we become disabused of the fantasy that all selves yearn only, or even mostly, for coherence, legibility, self-governance, agency, power, or even survival. Such a destabilising may sound hip, but it can also be disquieting, depressing, and destructive.”

Her new book, Like Love: Essays and Conversations, gathers a collection of works dated from 2012 to 2023. These are, as the title would suggest, essays and conversations, but their form and subject matter is various and sprawling. Eve Sedgwick, Hilton Als, Simone White, Fred Moten, Carolee Schneemann, Eileen Myles and (thrillingly) Björk all make appearances. The texts are arranged in chronological order and even if the dates were not explicitly stated at the conclusion of each, it is possible to construct a timeline by closely examining the evolution of Nelson's various literary works. Ideas are passed like precious stones, exquisite and robust, warmed as they progress from hand to hand; each held up to the light then skimmed across the sea—leaving a rippling imprint—only to wash up again on a different shore, glittering and resilient. The idea of time surfaces in Nelson’s interview with Jacqueline Rose, which we discuss here over Zoom. Time comes up again in the conversation with Eileen Myles, the very last text in the book, where they trade perspectives on a life lived in writing, “writing about time through time,” as Nelson explains.

In one of the essays titled ‘The Call,’ Nelson puzzles over Judith Butler’s line, “Let’s face it. We’re undone by each other. And if we're not, we’re missing something.” Peeling back the layers of these three short sentences, she unravels that our capacity for undoneness, whether through love, pain, injury or struggle, is never an isolated event. It is amorphous and extends between us. Each of us, ourselves perhaps the most complicated, messy knots of all, are inextricably intertwined with one another – an undeniable fact of existence, and any attempt to deny it is futile. Nelson reminds us that there is courage in facing these knots, that “writing and reading—if undertaken with requisite degrees of honesty and rigour—can counter this disavowal and denial. They can be a way of facing things.” As anyone with a pair of wired headphones will know, pulling on a thread from a tangled mass often only binds it tighter, only draws its floundering tendrils closer, more stubbornly together. Yet despite this, and despite the inherent risk of unravelling, trusting and pulling on the threads, even with the knowledge that they may reassemble, is challenging but important work.

Caitlin McLoughlin: Hi Maggie. Congrats on the new book.

Maggie Nelson: Thank you so much.

I loved it and I'm a big fan of your work. I’ve heard you speak previously about how ideas that have emerged over the course of writing one book have led you to the next. However your new book Like Love, is a collection of essays, interviews and conversations from over the last decade. What was putting this book together like compared to your other books? What was the process of looking back on your work and how your ideas have evolved?

It was super fun. I think because I’m a formalist really. At first I was like, how am I going to live with this motley bunch of essays? because they each had their own form in terms of how they were written. Then when I decided to put the conversations in as punctuation pieces in between the essays, it felt to me like it was really about making a mosaic of different ways of being in relation with other people's work and thinking. I think part of having the conversations in the book, which veer more into the problem of living, not just the problem of making and writing, is that there's a lot of kinship between how to live a life in art and writing and how to be alive more generally. I liked the conversations with people where there was a lot of flow in between those questions, whereas the essays are a little bit more focused on what the effect of someone's work is.

In terms of themes, certain themes come up over and over again and I edited very lightly, just to make sure that I hadn’t actually repeated myself verbatim. But it is okay with me to see and to know that some of the essays and conversations are working the same idea, especially because one never comes to the end of a conversation about gender or sexuality, or the relationship of art to language or the other things that recur in the book. Those are not questions that we're waiting with bated breath to be settled. They're just ongoing, exciting situations.

Friendship feels like a throughline that underscores a lot of your books – I’m conscious that you’re not someone who writes their friends out of their work. How do ideas around friendship influence your work?

That's a good question. I guess one thing that occurs to me is that there's a negative version of getting to know the people that you're writing about, which would see it as—what's the word— clubby? Or like the formation of cliques. But I think there's something much more interesting that goes on, which is that to meet somebody who you didn't really know well by being asked to behold and interpret their art, is very holy (for lack of a better word). Because ostensibly, their work is one of the most important things to them and they’re opening the door to that, which is why I say in my thank yous, thank you for inviting me into your worlds. It's like, tell me what you've read, tell me what bothers you. Tell me what you think about, tell me what you see you're doing. Show me your early sketches. It's very intimate in that way. We live in this world where—I don't know whether it's through social media or elsewise—people have a lot of interactions with people's work with no attempt underneath it to actually understand that person and what they might be getting at, much less appreciate it. It seems to me it's not just about making friends, but it's about a practice in your life where you do a little bit of emptying to hear somebody else, and then you return to your own voice in your room to think about what they tried to tell you or what you saw on their canvases or in their videos or whatever. I really like that whole practice, and I think that attempt to understand people and what they're trying to do or make, and combining that with what you see in their work... as much as I can, that's what I would like to be spending my time doing.

Some people, like Jacqueline Rose, I had never met before, so it's not like all the conversations [in Like Love] are with people that I know well. But once you start thinking and talking with them, then—it’s like I say in the introduction—you’re creating clouds together. Neither of us really has to be the one holding the opinion. We're trading the sound of opinions and trying them on; seeing how and why we might come at something differently. I think that's also a practice that both undergrids friendship and also undergrids, hopefully, a lot of intellectual thought.

Trust, almost. Is it building trust?

I mean, it’s easy for me to talk about building things with people or about trust when there's nobody to be in disagreement with. I don't spend any time in this book talking to anybody that I think is in bad faith or I don't talk to people who are bigots. There are a lot of people that I'm not going to rehearse a conversation with, so certainly there's a ticketed entry to all this. [Laughter]. But I think that even within that world of things, whether it's Moyra Davey and I differing on shame, or Jacqueline Rose and I having different reads on certain things in politics, or my friend Brian Blanchfield and I saying you keep using that term, but honestly, I don't know what you mean. We're all different people.

I think that stuff is all really pleasurable to read. In the way that it speaks to an openness or a vulnerability and that yeah, we're all different people.

There are these moments in many of the conversations that I just really love, like when I'm talking to the writer Simone White about the word care, and she says, honestly Maggie, I don't even know. She's like, I asked you about it, but I don't even know how to answer the question because given all the sexism and racism in the world that disciplines my experience, I can only understand this word in a very intimate and micro sense, and I don't see how it will scale up. When someone says I don't even know how to answer that, I really like those moments.

I particularly loved the essay on Ben Lerner’s novel 10:04. You open, like he does in the novel, with the feeling conjured by an impending storm and the strange sense that something is about to happen, that we are somehow about to be changed. It’s funny, I read that book at the very start of the pandemic as they were just about to announce lockdown and before anyone really knew what the implications might be. I remember reading that part as I was on the train and seeing the feeling he describes reflected in my surroundings. There was this bizarre sense of connectedness, like everyone was in on the same secret. Even though it was an unnerving, uncertain and in lots of ways terrifying time, I felt this strange excitement or giddiness, that I think was directed towards this sharedness or interdependency that is so often deliberately hidden from us, but in that moment was revealed or exposed. Part of what Lerner is doing in this book, as you point out in your essay, is examining or excavating these moments; “Paying as intense attention to our collectivity to our individuality.” I feel like this is also something you’re doing in your work – attending to our interior experiences as much as how we relate to one another. Why is this such a worthwhile pursuit?

I think there's so much theorising about—whether it's neoliberalism or late capitalism—the different forces that atomise the individual and the lack of infrastructure for community and all these different things. I think that they're all true, but I guess that I feel like all the critiques in the world don't really do the same labour as building something different. Even as we make those critiques, I feel a duty to grow for myself and then maybe exemplify in print, [the idea that] if you can't create relationships or community from thin air, start where you are and look at what you can make more of. I think a book like 10:04 is dramatising, just as you described it, that kind of back and forth—it's not like there's going to be one single community moment that sustains in a city like New York—so the narrator is going back and forth and trying to participate in different things like at the co-op or with the Occupy protesters. But they're all not good enough because no single person can overturn the structures that they live in and because the narrator is very contaminated by his subject position, he knows all that. And yet, interestingly, at the end of that book, the symphonic community is via a necrosocial connection to the poet, Walt Whitman. It’s not in a circle holding hands with other New Yorkers. It's feeling the continuity of Whitman's poetry across time. I do think that there are many ways that we can recognise ourselves in a community, even with the dead. I think in Lerner’s case, and who knows if they're sustaining for him or sustaining for that narrator, but for us in reading them, they awaken a feeling that we can then look at how we might sustain. Particularly amidst all the forces that work against it. All of the hideousness in the opening of that book, with the expensive lunch and celebrating capital for art and with the octopuses massaged to death, it's all very bleak. He's so onto the fact that he can write that critique really well, but he's not willing to just let it stop there as a cynical, well drawn critique. I think that's the risk. It's riskier to try and be like, and what else? I see his art, and a lot of other people's art, as often taking that risk.

I think that feels like a lot of what you're doing in On Freedom, where you situate the ideas of freedom that you're exploring in the present, rather than in “some revolutionary future that may never come, or in some idealised past that likely never existed or is irrevocably lost.” Could you talk about why that was important to you?

I mean, it's hard work because it's more rhetorically satisfying to do critique, or to do utopian writing that says, here's the world we could be going for. Both of those things absolutely have a place, but I'm always on the alert for how shame can step in to thwart our personal or even political aspirations. I think sometimes the present can be inadvertently treated as a shameful place to be and I don't know that that's the most empowering place to move from. The lay Buddhist in me is like, here we are. We can't skip over where we are. Critiques of Buddhism or other ideologies that focus on the present have always been that people fear they're going to legitimise the injustices that exist in the present. But I don't think that... a lot of On Freedom was written in a sense of accepting that we are where we are is not the same thing as not striving to make anything different. It's why people so often use the metaphor of planting seeds, which I talk about in On Freedom. Planting seeds is a present activity, watering seeds is a present activity. It has a hopeful element towards the future, but it also understands that we don't know. We don't know if we picked the right seeds. We don't know if they're going to come up. We don't know if a meteor is going to hit and take away all the soil. We just don't know. But that doesn't mean that we can't be here, now, planting those seeds.

This idea comes up in your conversation with Jacqueline Rose where you quote her: “if there is one thing of which writing about violence has convinced me, it is if we do not make time for thought, which must include the equivocations of our inner lives, we will do nothing to end the violence in our world.” She defines thoughtfulness as the ability to have a reckoning with what you cannot control or master or know fully. For me that feels very connected to this idea of time and creating hope in the present.

It's really interesting that you pulled that out and heard the 'time for thought,' because in talking with her I was very focused on the 'thought' part. But now that you read it out loud, it seems really wise to hear the whole phrase, because thought does take time. In On Freedom I talk a lot about time and about the agony of thought taking time. Something like the climate crisis, as Bill McKibben says, it's one of humanity's first timed tests. We don't have all the time that we might like to have to plant the right seeds. I think that puts intellectuals, but not just intellectuals, in a tough spot. I think Rose's definition of time for thought and what you just described about holding equivocations, it's very interesting to me because it kind of sounds like she's talking about feeling – feeling contradictory things and holding them, not just thinking them. In that case, it's not just intellectuals, it's a difficult time for everyone.

One thing I think is true is that, this sounds kind of paradoxical, but if you've given yourself time for thought, even when something happens that requires a fairly immediate response—again, this is a kind of a Buddhist practise—but inserting even just a few seconds in between reaction and action, can immensely change the outcome.

It might be just the amount of time that, say you're angry and you're about to do something in anger and you think, I'm angry, but I love this person, even just that thought might be enough to divert the action. I'm on a tangent – I don’t think that the climate crisis is going to be solved by interpersonal decisions about anger. But nor do I think the frustration at what's reading a long book or writing a long book going to do to help solve the climate crisis is very helpful, in the long run. If anybody reads that chapter [in On Freedom] and feels a little bit less paralysed, then I think that is one thing I can possibly offer. It's not a policy prescription, but it's what my skill set might have to put into the wind. And it took time.

There's this other Jacqueline Rose quote, which is from her book The Last Resistance and it was part of the inspiration for this issue, which is themed around psychoanalysis. “It often appears that the role of writing—fiction but also non-fiction—is to push you right through what should be the impassable boundaries of the mind.” Do you feel this is your experience of writing?

No, it's not. [Laughter]

There's a quote that I use in On Freedom from British artist Sarah Lucas where she talks about making art as being trapped in a jail cell with a nail file, and then Wayne Koestenbaum has talked about the way as soon as you start a sentence, you're in jail. You're in the jail of grammar. My partner's an artist, and he'll be excited about working with aluminium, and then he'll come home and be like, man, fucking aluminium. So if it comes out as pushing into a previously unknown world or making a world possible, it's out of a very strange alchemy with limitation. I think that is much closer to the actual experience of making. But that's also the miracle of making, that you could be fighting all that and then, when I hear Wayne Koestenbaum read his poems, I feel an immense sense of possibility. If I see Sarah Lucas' sculpture, I feel an immense sense of possibility, or boldness. But it doesn't correlate that the artist feels free, and that's okay. Because, as it should be,

when you're actually interfacing, you're not just imagining in your head what literature can do, you're interfacing with other material like the material of language or the material of metal, and it's not going to yield to you without a compromise between what the two forces want to make.

Do you think that quote then could be the experience of reading?

Yeah, I do. Maybe there are some writers who feel a radical sense of possibility while they're writing. I would argue they probably feel that after having written maybe, beholding what they got to. You’re usually just trying to solve a book, where every sentence sounds right to you and is in the right order, and that the right parts are there and the wrong parts have been taken out. Then what it is to other people, what all that aesthetic obsessiveness has done is not really, I think, a thing that you can work on directly. You can only work on the micro, and then if it's bigger than the sum of its parts, that’s, I think, for the reader's experience. I think that's why they say writers abandon books, they don't finish them. I think that's generally true. Though, the hope is that you abandon it when you see that no more can be done, but it’s kind of as good as it gets.

I want to come back to this idea of shame and your conversation with Moyra Davey. I was talking to my friend about this last night and she reminded me of an Annie Ernaux quote from Simple Passion: “Naturally I feel no shame when writing these things because of the time which separates the moment when they are written – when only I can see them – from the moment when they will be read by other people, a moment which I feel will never come.” She then goes on to say, “It’s a mistake therefore to compare someone writing about their own life to an exhibitionist, since the latter has only one desire: to show themselves and be seen at the same time.” Moyra Davey says that to her you seem shameless, because you can write about anal sex or whatever. But you make the point that you don't really think of your writing as existing in a matrix of shame and exposure and revelation. It made me wonder, when it comes to shame, is revelation the same thing as transgression?

I think that Annie Ernaux quote will be very familiar to any writer. I mean, a book goes into a lockbox; you turn it in and there's a year of it going into production, of copy editing, proofreading and picking out a cover, and that's true of Taylor Swift records, it's true of anything. There's always a lag in between the moment of confession and the thing hitting the world. So to me, if it seems like a revelation or if it feels like it has the heat of something intimate or immediate, then that's just a sign that the aestheticism of the writing has worked, but it's actually an effect that is conjured. It's not a given truth. You're also aware, which nobody else is, of all the things that are on the cutting room floor. The opening of the Argonauts to me is a formal gesture to announce that this book is going to be about both bodily experience and ideas about language, and it’s to try and put them into close context so that you know what kind of book you're reading and what issues are on the table. This fantasy of transgressive revelation – it's not quite where the writer usually is.

To me, it almost feels like thinking about shame after the fact or after the event maybe, doesn't cover all of what the experience of shame is.

Yeah.

I would say being a writer in public and being called to respond to the words that you’ve written really has a lot to do with the practice of contending with other people's projections of shame upon you, and that’s a different skill set than grappling with your own shame.

These things can overlap, but they can also be very distinct. Because I know what my shames are, what my private struggles in my life are and then there's things I don't really feel ashamed about in my writing or anything. But you're having to learn how to manage what it feels like people are telling you about themselves. I got at this in the essay about Hervé Guibert [in Like Love] and how a lot of writing about him that's outside of the milieu that he came from really misses the mark in terms of thinking that he’s out to shock the bourgeoisie. Without it really occurring to them that they're revealing their own prudishness when they're telling you that they find the life this person's living to be beyond the pale. Or that the sex that they're having, they’ve never heard about, and I'm always like, sounds like you should get out more or whatever. [Laughter]

Whereas to me, I'm like, great, let's go. But if you look at the critique of personal writing, you'll notice, and this is why I think Eve [Sedgwick] was really onto something, that the words self-indulgent, masturbatory, self pleasuring, selfish, all reveal a distaste for the idea that

writing could be an act that pleasures the writer first and foremost, and then lets the chips fall where they may in the world.

That sounds great to me. I don't have any problem with that whatsoever. Especially if you work a lot with artists. I taught in a visual arts school for 12 years, and in some ways you're teaching people how to be self-indulgent, but by which I just mean to take their ideas seriously. I talk about this in the long essay about Carolee Schneemann, about how she lets herself be at the centre of rays of relation passing through her. A lot of people, especially a lot of young artists, are struggling to think that their ideas matter or that the world will care about them, and there's a certain confidence that you're trying to instil in them that words like self-indulgence just exist to batter them as they're on that road. I don't find it very useful.

It's kind of like the Sedgwick quote you use in On Freedom: “you can say that?” It's permission giving.

Yeah. Because whether or not something began as self-indulgence is not what's going to determine if it's good art or not. There's a million other formal things that determine whether a piece works. I think often when people don't like something, they're responding to something else that didn't work, but they're naming it as self-indulgence or personalness or whatever. Also, it's not for everybody. Annie Ernaux has passionate readers and some people don't like that kind of work, and who cares? I don't love sci-fi, what does it matter?

Teaching feels like something that's important to your writing. In your conversation with Brian Blanchfield, you ask “is truly experimental pedagogy that which—like good therapy, perhaps—adapts itself to the particular humans at hand? How does the task of the teacher change in a culture where reading, writing, and thinking themselves—radical tools, it seems to me—have become whipping posts, tagged as potentially dispensable in whatever wacko phase of capitalism we're in now?” I really love that quote and wondered how you feel that your task as a teacher has changed in response to the shifting landscape of the university under capitalism?

It's interesting because I think at the time that conversation took place, I was teaching at an art school and the relationship to the role of reading or writing in art school is really different than in a liberal arts university. So I think in addition to that quote about the student and how the student changes the teaching it's also—as I've learned now, moving from several different institutions—a question of how does the task change given the nature of the institution that you're in? That has a lot to do with the material conditions of students.

Teaching at art school was very spiritually rewarding, in that it was a very good match for the way I wanted to live and be around people, but it was not a wealthy school, so the students were paying high tuition and financially suffering by getting into debt. Whereas now I teach at a much more wealthy school where a lot of my graduate students are paid competitively to be students rather than getting into debt, and yet you have all the problems that come with being at a wealthy institution with a lot of power. So I think there's a lot to take into account, not just the intellectual situation of students, but their material situation and things like that. That's all really interesting. I think at the time I said that in that interview, I was concerned that my students' rejection of the value of reading was echoing a very strong anti-intellectualism. A figure like Sarah Palin was in the mix at that moment. I think that has continued, although now, with having my own kids and stuff, I think that a kind of nostalgic cri de cœur about the fate of reading in the world of the smartphone or whatever is not the most useful subject position to hold. The attack on American universities that we see going on in a very intense fashion right now, that's been going on for some time, but vis-a-vis the war in Gaza, has become much more intense in the last year. I think the kaleidoscope keeps turning on both what we're doing from the inside and then also what forces are coming down to try and warp or defund or put an end to the mission of reading and writing together. So there's a lot to think about there.

It feels like there's the sense that, and I think we're really seeing this right now with what's happening with the Palestine protests, the institution and the student body are diametrically opposed to one another. As a professor, you’re caught between these two camps, often aligned with the institution by the students, but ultimately just as much at the mercy of the institution as the student body, how do you navigate that position?

My own experience has been that I knew from the start that I wanted to be a writer. That was the goal. Whether or not that would mean I was a teacher or that I would manage restaurants or whatever. Then I think by working in an art school—which was just luck of the draw, no one hired me at a regular school after I got a PhD—I missed some of the academic indoctrination that might've gone on. So, I don't know. I feel like I spent a long time trying to ignore the institutions in which we do our work, but now I’m thinking a little more about them. I mean, I’m not a kid anymore, when you’re just struggling to get a job, pay the rent, roll pennies, etc. So I think I have the privilege of thinking more about institutional questions that, maybe heretofore, I felt on the run from. But my first fidelity is to be a writer. I teach in a creative doctoral programme, which means that instead of a short term, two year creative writing course, which is what I taught in for over a decade, this is a longer five to seven year engagement that entails a little bit more intellectual rigour from our creative students, but it's still anchored in creativity. Because of that, and it was the same in art school, the pressure on whether or not I’m professionalising people to continue to be part of an academic structure is not a given. Whereas I think in other spheres it might be more so. In that way, I feel like I'm teaching people how to be better writers and also how to make their writing come first for them. I don't mean over their children or whatever. I just mean if they choose to commit to it, what a life lived with that as a practice and as a commitment might entail from them, psychically and materially, and that's a little bit different – it's a different project. And yet of course we’re still in the world, we’re still a part of these institutions, and we have to think about that too. Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s work has been important to me here, as has been the example of so many artists and writers and radicals and intellectuals who negotiated these spaces before me, and who negotiate them now beside me. We’re in—and out—of these things together.

Maggie Nelson is the author of several books of prose and poetry including The Red Parts, Bluets, the National Book Critics Circle Award–winner The Argonauts, and On Freedom. She teaches at the University of Southern California and lives in Los Angeles.