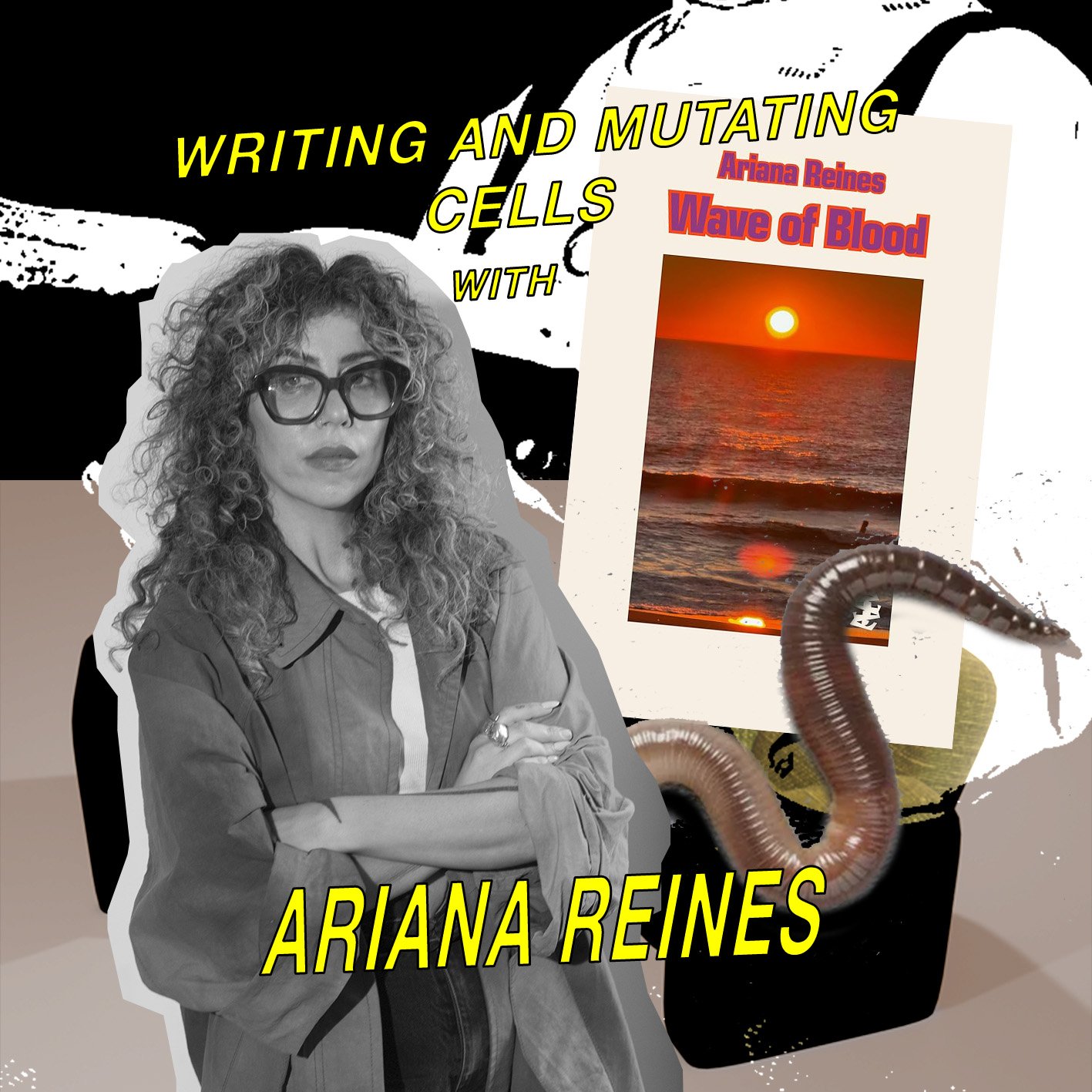

Writing and Mutating with Ariana Reines

A writer who hardly needs an introduction, Ariana Reines has published an array of books, A Sand Book, The Cow, Coeur de Lion, to name a few, which have touched readers across the world with their ferocity, sincerity and unwavering commitment to the power of words as vehicles for truth and transformation. Her newest book, Wave of Blood is an amalgamation of poems, journal entries and transcripts of readings she did on a book tour in Europe during October 2023. It has been described as “poetry of witness”, and reading it is to be a witness too; not only to Reines’ family history as she retraces their past in the lands where her family faced extermination in the 20th century but to the vast suffering that presently plagues the world. Reading it, I had the acute sense of holding an object sizzling with life in my hands, a vital piece of work, a reminder of the uses of poetry at times when horror risks paralysing one into the worst of all possible reactions: inaction.

Arcadia Molinas: Wave of Blood feels alive like few books I’ve ever read. There’s an immediacy to it, as if it was written in a kind of fever. How does it feel to revisit the book now? Has your relationship with it changed over time?

Ariana Reines: I’m glad it feels alive to you—and I did actually have a very bad fever when I was finishing the book last April. There was a moment during that fever—I had stopped eating, and had been running a temperature of 103 fahrenheit—that I heard a voice. It said: That’s too much suffering. Stop it. It’s a bit of a strange story to tell, and maybe sounds overly simplistic, but it felt like, recovering from that fever, I was mutating. Like my cells changed their relationship to suffering—my own and the suffering I see in the world—forever. It felt like everything inside me had to change in order to finish the book. It feels like a neutral document to me now.

Do you have a sense of what cells mutated inside of you—which cells died, and which came to life?

All of them.

You open the book with a quote, almost a cautionary statement, from Etel Adnan, “Science must not replace pain, because when that kind of a catastrophe happens, it has no mercy.” Could you expand upon the relationship between science, pain and mercy that Adnan lays out here?

I chose this line because we are at an inflection point culturally, as machine learning and AI expand. Part of the way I understood Wave of Blood was as an investigation into suffering, and an attempt to take very seriously the role of suffering in the development of human consciousness, over the course of a single lifetime, but also, dynamically through all time.

You write about John Milton’s Paradise Lost in the context of reading it at your community-led project, Invisible College. Could you expand on the effect of reading poetry as a community? What transformations take place in that shared experience, and why might it be necessary—or even vital?

Invisible College is a fascinating space because it’s full of artists and musicians and writers I deeply admire. Studying Paradise Lost was my first time teaching something I really didn’t have a lot of previous experience with, and something I knew I probably wouldn’t have gotten all the way through or read as closely without a community. It really is a mind-blowing poem and the experience of studying it has changed my consciousness, in at least five ways, especially around the way Milton sees free will.

Invisible College emerged from an earlier project I’d done in 2012 and 2013, called Ancient Evenings, to change my relationship to the reading and study of poetry through sacred and ancient texts. Back in 2012 I personally felt my life depended on finding a new way not only to read, but also to write with people. I was very much building on a kind of New York School / Saint Marks ethos, which I’d absorbed through a teacher of mine, Paul Violi, and some of my favorite books. I can’t tell anybody what should be vital for them, but doing this kind of work with brilliant minds in a non-university context has definitely been vital for me.

You describe poetry as a source of “information—about the meaning of life, the structure of the soul and body, and the dynamics of the cosmos.” What other “sacred texts” or poems do you turn to when seeking this kind of insight?

So, I’ve noticed that some poetry seems to be encoded somehow with what we could also understand as “information” — like data, about the structure of the universe, the nature of the soul, the meaning of life, and so on. This encoding is sometimes metaphorical, sometimes rhythmic or musical, sometimes quite literal and direct. I started to notice this about twelve years ago, when my own suffering was really driving how I read. I noticed that certain texts actually had the power to make me feel more balanced and grounded inside. Not just in a kind of superficially comforting way, but in a rather mysterious, undeniable way. I became really curious about that. I’m still really curious about that. Everything I’ve taught in Invisible College is in my personal pharmacopeia: my favorites from the Nag Hammadi Library, Rilke’s Duino Elegies, Joe Brainard’s I Remember, the Song of Songs, and so on.

I want to know more about how space and place filters into your writing process, specifically in the context of writing Wave of Blood, in Europe, visiting countries where your family and people were exterminated amid the horrors of the ongoing Nakba. What does embodiment mean to you?

All I can say is writing is much more physical than I thought it would be when I was a toddler, scrawling the letters of the alphabet on the back of my headboard. I have a very early memory of imagining the life of a writer and I thought it was so cool that basically, a writer was just a name, and language didn't even necessarily require a body. I thought it was amazing that a human being could be immobilised, or have no limbs, or be a giant worm like Jabba the Hutt, and still write.

I really feel like our bodies, everything about them, the struggles and pain, and also the sense of joy and rapture, has everything to do with how we create.

And as a child I loved the idea that a writer or writing could somehow be totally free of or separate from the body. That I could somehow give up everything, even my own limbs, and still do it. A child's thought. As it turns out my experience of writing has been totally physical, and very physically demanding, maybe because of my background in classical dance.

I’m fascinated by your framing of poetry as an alchemical process—a way of transmuting grief, rage, or despair. To me, this feels like one of the essential promises art offers: to mine personal uncertainty and pain, and transform it into something else. But Wave of Blood revealed to me that this alchemy is not limited to the individual—it resonates beyond. How has your understanding of this transformative process evolved throughout your practice?

I think Baudelaire turned me on to the idea of alchemy. When I was in my twenties it was really out of fashion to admit that art could be in any way therapeutic, this was seen as a feminising insight and any artist who wanted to be taken seriously had to reject the question of any transformative, alchemizing, or therapeutic dimension to their practice.

Writing Wave of Blood was a painful experience for me, and also a record of a horribly painful time, but obviously I knew that my pain was nothing compared to that of children, families, a whole world ripped to shreds before my eyes. And I also knew, as we all do, that it is impossible and pointless to compare or weigh pain against pain, though we also can’t help it. I absolutely could not have any hope that reading an account of me wrestling with my own personal agony would be of any use to anyone, but at the same time, if I didn’t hope it might somehow be useful, I wouldn’t have been able to write the book at all.

Ariana Reines is a poet, playwright, and performing artist from Salem, Massachusetts and based in New York. Her books include A Sand Book (2019), winner of the 2020 Kingsley Tufts Award and longlisted for the National Book Award, Mercury, Coeur de Lion, and The Cow, which won the Alberta Prize from Fence in 2006. Her Obie-winning play Telephone was commissioned by The Foundry Theatre with a sold-out run at the Cherry Lane Theatre in 2009. Reines has created performances for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Swiss Institute, Stuart Shave/Modern Art, Le Mouvement Biel/Bienne, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and Performance Space New York. She has taught poetry at UC Berkeley (Holloway Poet), Columbia, NYU, and Scripps College (Mary Routt Chair), been a visiting critic at Yale School of Art, and for community organisations including the Poetry Project and Poets House. Her poetry and prose have been published in The New Yorker, Poetry, Artforum, Frieze, Harper’s, and others. In 2020, while a Divinity student at Harvard, Reines created Invisible College, an online space devoted to the study of poetry, sacred texts, and the arts.

Arcadia Molinas is a writer and performer based in London. She is an editor at Worms.