2022 Best Reads of January

PIERCE

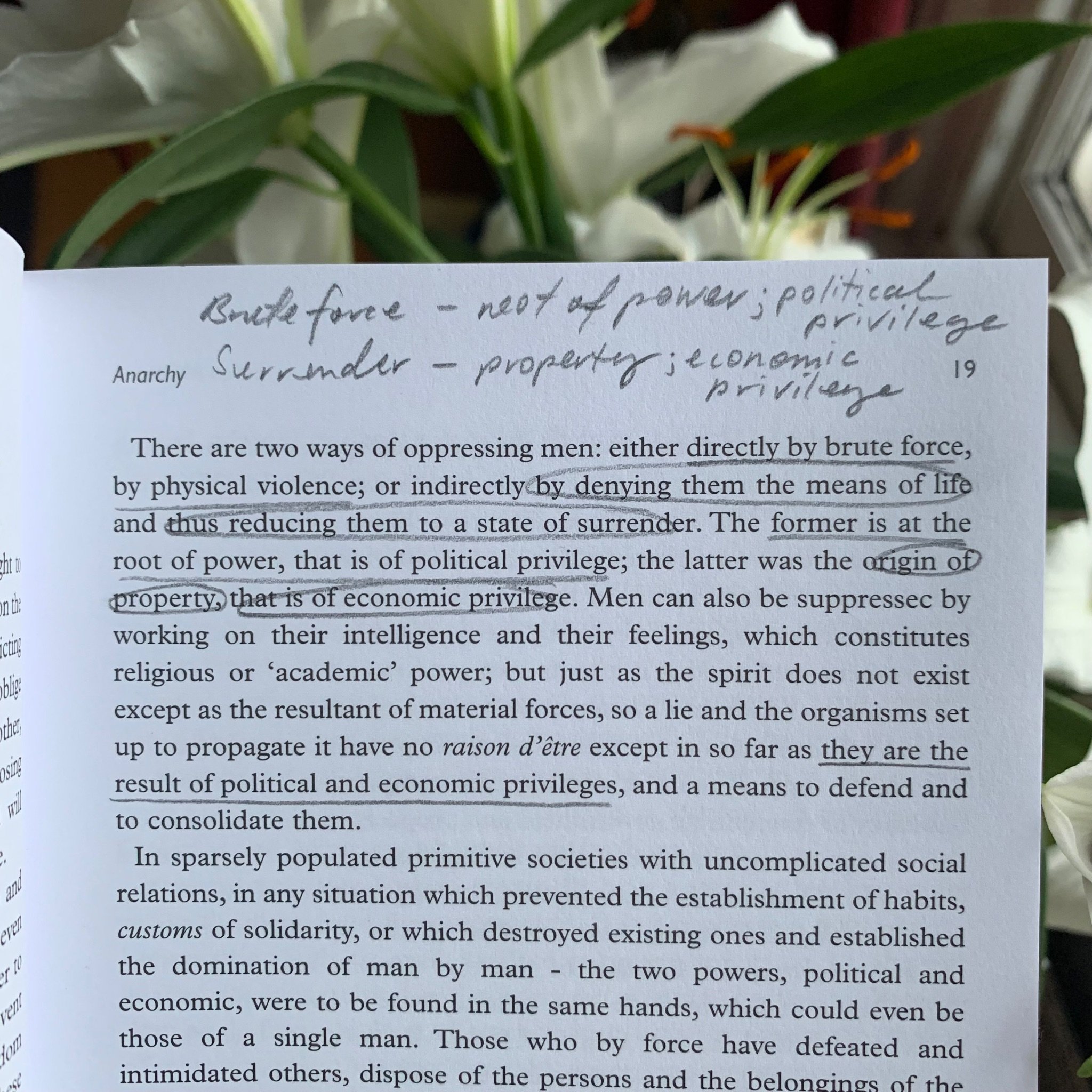

I’ve been going to a lot of freedom, abolitionist, anarchist, and queer bookstores around London lately, which feels like a nice way to explore the city by bike; radical bookstore to the next. At Freedom in Whitechapel, I picked up Anarchy by Errico Malatesta and it’s a very thorough introduction to anarchist principles. I’m gravitating more and more to these types of books, I think because they provide me with foundations on how I might come to reimagine the world around me through the ethics of interdependent mutual aid for all via the abolition of the state. This was first written in 1974, and I think the concepts are still being reconfigured today in our society as more liberating movements are becoming a healthy mix of socialist, abolitionist and communist. I think, in a way, it still is very contemporary and is known to be one of the larger bodies of work Malatesta spent time on, which is fascinating too because it’s a very quick yet informed read. I am, although, extending my reading and looking toward more queer, trans, and feminist writers on these topics. Stay tuned.

Hilariously, I’ve been really craving some delectable, insatiable, queer fiction, so I grabbed I Look Divine by Christopher Coe and it was so boring. I wrote a review on Good Reads and I’m literally, word for word, just going to paste that here because I think I nailed my initial response: ‘I really wanted to like this but it was so boring, omg. The synopsis made it sound v-lavish, v-fancy, v-full of life, but Nicholas is so unappealing and tiresome. Huge yawn, the cover art is so cute tho.’ Defs not best read, mwah x

CAITLIN

I read this one over the new year, which felt fitting as it’s an already reflective time, where you feel momentarily stuck between the recent past and the distant future. Described as a ‘collective autobiography’, The Years is Annie Ernaux’s narrative/memoir/life’s work that traces events both global and intimately personal between the years of 1941 and 2006. Reading this book is like being on a very long car ride that you never really want to end. Wars, great storms, presidential elections, technological advancements, fashion trends all wash over you in sepia tinted haze. No distinction is made between these events and the events of childhood, secondary school, university, work, children, divorce, lovers, menopause, retirement – a lifetime, rendered in shimmering prose, that passes you by in a continuous, fluid stream. It's written in a seamless mixture of the first-person plural and the third person—‘we’, ‘us’, ‘she’, ‘them’—it's intimately communal, yet keeps you at arms length. Descriptions of photographs occasionally pause the narrative, the “little girl in a dark swimsuit on a pebble beach” and the “middle age woman with reddish-blonde hair and a black low-cut jumper”, snap-shots of family life. I found the passage in which she describes the continued ritual of Sunday lunch following the divorce from the father of her children particularly moving: “we wondered what bound us to each other. It wasn't blood or genes, only a present comprised of thousands of days spent together, words and gestures, meals, car journeys, a great deal of shared experience that left no conscious trace,” only to zoom back out and recall a terrorist attack at the Saint-Michel Métro station in 1995. The engulfing creep of consumerism is ever present: “the acquisition of things (which we later said we couldn’t do without) was more and more life’s magnetic north,” and intensifies as the 90s and then the new millennium emerges. On occasion I found myself questioning her stance, which highlighted the limits of illustrating a collective history from what is ultimately a singular perspective, though with Ernaux’s assured self awareness, as a reader you understand these limits as she does: inescapable. What’s universal is the slipperiness of memory, the fear of forgetting and being forgotten – the uncertainty of the future, bitterness towards the past, the need for intimacy in the present. She rejects the urge to summarise and rather she simply observes, capturing the perpetual contradiction of the present moment, the friction between hopes and realities, the frisson of constant change. Life’s inevitable, simultaneously relentless, terrible, joyous forward march.

CLEM

How Should A Person Be? By Sheila Heti

Holy shit I can’t remember the last time a book made me LOL like Sheila Heti did in ‘How Should A Person Be?.’

I read Heti’s ‘Pure Colour’ after she had been raved about by so many, and truly did not get the hype. I actually don’t know what it was that made me pick up this book, considering my experience with her last, but I did, and I’m so glad that I did. Heti is smart and witty and HILARIOUS. It’s like she has absolutely no shame whatsoever. I envy her for that. There are definitely bits that are a bit questionable, and that I wouldn’t necessarily agree with, but in a way I respect her even more for being able to publish those bits without fear of what people might think of her. The amount of shit talk that she indulges in is completely admirable. While funny, it’s also quite profound too. She uses these comic masks and slightly unhinged characters (based on herself…) to communicate her ideas about the world, and in particular about being an artist and writer. The thing that stood out the most for me was her repeated questioning of whether she was a writer because she felt it was her purpose and calling, or whether she thought that it was the cool and right thing to be. I really wonder how much of the dialogue is taken from real life conversations too, considering a big dispute she has in the book is about using her friends for material for her play. It seems she’s done just that in the writing of the book… My favourite line… “He’s just another man that wants to teach me something”

I’m not sure I would recommend this to an older audience. I think it’s quite specific to the twenty-something reader that I feel it might be aimed at. Although in saying that, I’ve given it to my mum to read, purely because I thought she would find it funny. I wouldn’t necessarily say that it’s going to ignite any late-in-life revelations.

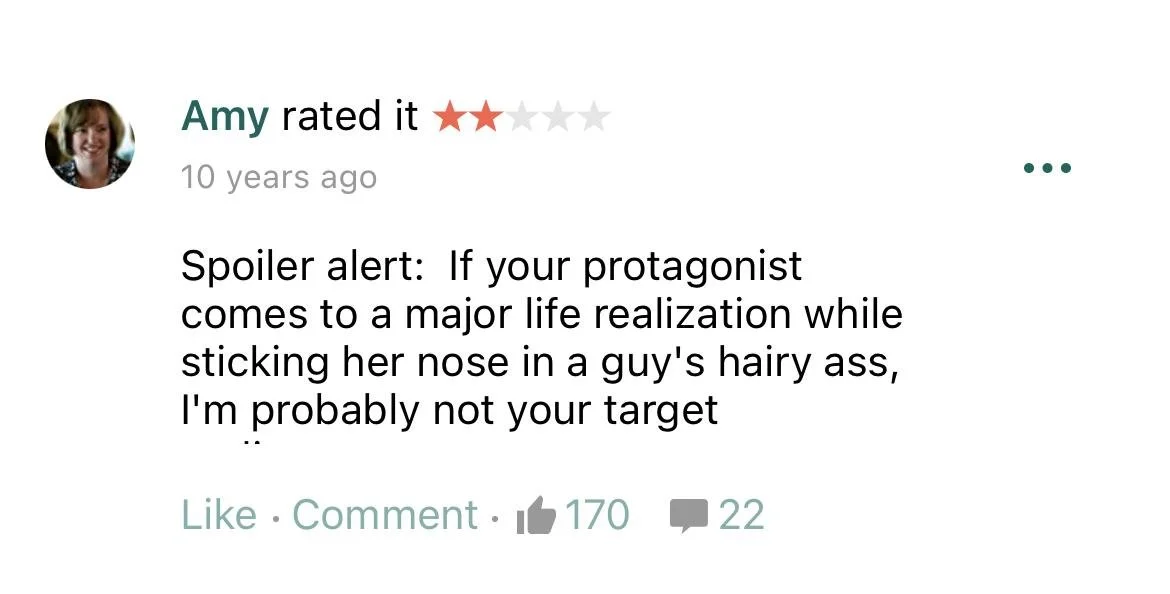

Oh and to top it off, when I finished reading it, I read a review that said ‘if your protagonist comes to a major realisation while sticking her nose in a guy’s hair ass, i’m probably not your target’ - as if it were pulled straight from a Sheila Heti novel.

ARCADIA

A Woman’s Story by Annie Ernaux

I was actually going to write about ‘The Years’, which I also read in January, but Caitlin beat me to it, so I’m going to review a tangential read, another Ernaux title that I enjoyed immensely, ‘A Woman’s Story’. I also read ‘The Possession’ by our Nobel prize winner which is arguably more saucy and extremely relevant with all that’s going on in the world right now (read: Shakira) BUT I found A Woman’s Story very moving and I suppose I feel a stronger pull at the moment for literature concerning families and depictions of parental relationships etc. A Woman’s Story attempts to objectively display Ernaux’s mother’s life, from childhood to her death. So in a way similar to The Years, her sweeping narrative takes us from point to point of someone’s life. The marvel of this book is the objective tone she maintains throughout, which is expertly crafted and inevitably plants questions in your own head concerning your own mother and your relationship with her. Do I know my own mother enough to write such a history?

Ernaux traces her mother’s upbringing, born into a working-class family and a small town which offer her two options: continue to work the land like her parents and their parents before her or go work in a factory and pride oneself off of economic independence. Choosing the later, Ernaux reveals her mother’s attitude towards marriage and sex, in accordance with the time in which she was alive. Throughout, is the tension between her mother’s class aspirations and her reality. After her parent’s first child, another girl, dies at age six from a sickness, Annie is born and given all the luxuries her parents were deprived off, namely, entrance into a private school. There, Annie explains that the confusion she felt being surrounded by other students whose parents were, as one of her guiding lights Pierre Bourdieu puts it, part of the dominant and not the dominated like her own parents were, is mirrored in her own relationship with her mother at home as Annie starts to adopt the language of the dominant and become one of them. The prose is interspersed with clairvoyant moments such as:

“I was sure of her love and this injustice: she served potatoes and milk morning through night so that I could be seated in an amphitheatre listening to somebody talk about Plato”

[my translation from the Spanish]

After Annie gets married, welcomes her mother home with her husband and sons and then gets divorced, her mother starts to suffer from Alzehimer’s (in summary). I was very interested in reading her experience of taking care of a person who once took care of you and the feelings that accompany this role reversal.

Needless to say, once I finished this I went to my own mother and told her I loved her.

“This is not a biography, nor a novel, naturally, maybe something between literature, sociology and history. My mother, born in the dominated world, from which she wanted to escape, had to transform into history, so that I felt less alone and fake in the dominating world of words and ideas that, as was her wish, I travelled into.”

[again my translation]