2022 Best Reads September

Arcadia Molinas:

Sick Woman Theory, Johanna Hedva

In this short, compelling essay, Johanna Hedva traces the development of their Sick Woman Theory; their illness, their diagnoses, their invisibility, “the trauma of not being seen” and how they came to powerfully contest Hannah Arendt's definition of the "political" as "any action that is performed in public".

"Sick Woman Theory is an insistence that most modes of political protest are internalised, lived, embodied, suffering, and no doubt invisible."

What happens to your political subjectivity if you are rendered immobile by illness? If you lack the care that your body requires (health care, accessibility, money for rent, legislative protection, support, validation, visibility) what happens to your force as a political subject? Sick Woman Theory takes issue with all these questions and refutes them with a call to arms.

I came across this essay mostly thanks to a t-shirt designed by Kaiya Waerea from Sticky Fingers Publishing, that sports this reading list on the front and the slogan “READ SICK WRITERS” on the back (not available as of now :( )

Endometriosis, one of the illnesses that Hedva has been diagnosed with (although Hedva prefaces her diagnoses with other ways of understanding her illness that don’t rely on Western medical terminology – astrology, generational trauma, poverty, queerness, etc), afflicts one of my close friends. In fact, it is estimated that around 10% of the population suffer from endometriosis. For the past four years I have seen my friend be rendered immobile once a month, suffer from extreme bloating and severe stomach pain. It was evident to me that so much of our world did not accommodate her day-to-day experience. In Sick Woman Theory, Hedva asks the important question in relation to this: “How do you throw a brick through the window of a bank if you can’t get out of bed?”

What follows is a fierce manifesto “for those who are faced with their vulnerability and unbearable fragility, every day, and so have to fight for their experience to be not only honoured, but first made visible.” The way they take issue and complicate pillars of knowledge is inspiring and badass (previously mentioned Hannah Arendt, Audrey Wollen’s ‘Sad Girl Theory’ and Kate Zambreno’s Heroines) but they simultaneously allow themselves to be embraced by like minded theorists to form a powerful alliance (Audre Lorde and Judith Butler among many others).

This essay can be read in an afternoon and is widely available. I suggest you make space in your calendar and squeeze in this essential read. Alternatively listen to Hedva read it, alongside an audience discussion at the end: “My Body Is a Prison of Pain so I Want to Leave It Like a Mystic But I Also Love It & Want it to Matter Politically”

Portrait of Johanna Hedva. Photograph by Pamila Payne. Styled by Rhi Jade.

“The most anti-capitalist protest is to care for another and to care for yourself. To take on the historically feminized and therefore invisible practice of nursing, nurturing, caring. To take seriously each other’s vulnerability and fragility and precarity, and to support it, honour it, empower it.”

Pierce Eldridge:

Archipelago, ÉDouard Glissant and Hands Ulrich Obrist

I loved the format of this book, a conversation between friends, colleagues; who share mentorship for one another in the form of regenerative provocation. The dialogue focuses mostly on French-philosopher Glissant and his literary interests of seeing an art world–and the development of a new museum–combined with more poetry. There is discussion on how to do so by building a new set of politics that are found within creolisation of the world, “archipelagic thought,” and the museum as archipelago, as well as utopia... imagining our worlds as big islands that need interconnection once again, building reliant and companion threads of kinship in language, communion and art-poetry. Felt very intimate to flip through, what I assume was, private conversations with sprawled poetry and drawings, and salutations in the dearest of tone. If you like pocket size, this is v-cute with mighty thought!

Ella Slater:

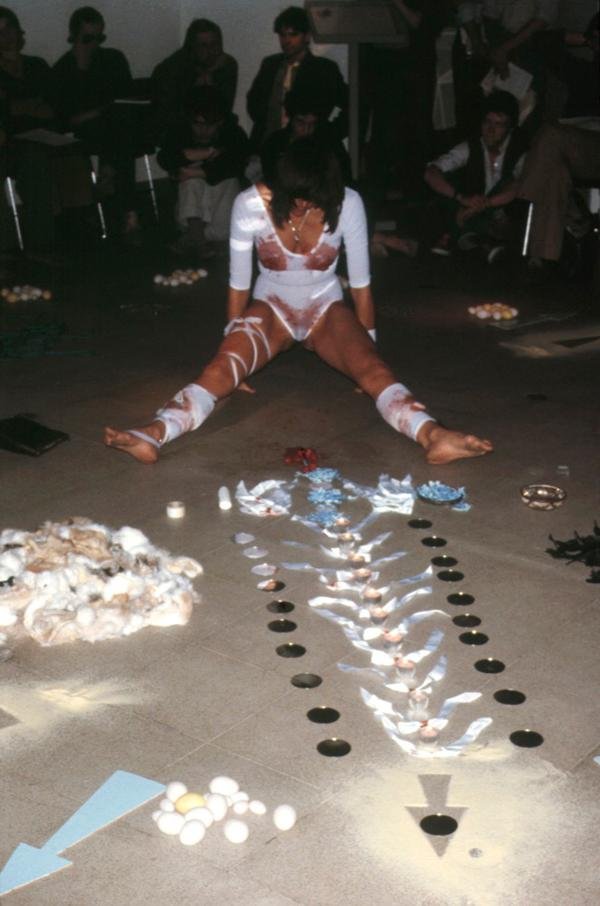

Cosey Fanni Tutti, extract from three-day ‘ACTION’, Hayward Gallery, London, 1979. Courtesy the artist and Cabinet, London

I’m currently mid-way through Cosey Fanni Tutti’s Re-Sisters: The Lives and Recordings of Delia Derbyshire, Margery Kempe and Cosey Fanni Tutti, published earlier this year. I’ve wanted to read her first book Art Sex Music for a while, but kept coming across Re-Sisters in various bookshops, which felt like a sign. Tutti, whose name is a twist on the Mozart opera Così fan tutte (which translates to “that’s what women do”) is known for her work in the 1970s art collective COUM Transmissions and later in the industrial music band Throbbing Gristle.

Re-Sisters is an account of the lives of three outsider women: the electronic musician Delia Derbyshire, who worked for years at the BBC’s notorious Radiophonics Workshop; Margery Kempe, a 15th-century mystic visionary who wrote the first English-language autobiography; and Tutti herself. They were and are all ‘difficult’ women – complex, stubborn and unconventional – which I found super inspirational. Although the book documents the societal constraints of the various periods each woman was born into, it is also a fierce celebration of individuality and selfhood. It reminds me of a quote I love from Dodie Bellamy’s Bee-Reaved, where she talks about Judy Grahm’s 1974 poem A Woman Is Talking To Death:

“Grahm reminds me that for a woman, too much is always a form of resistance, and I regain momentum.”

Caitlin McLoughlin

There is always so much bitterness and cruelty in the worlds that Ottessa Moshfegh creates. Lapvona, the fictional, mediaeval village that gives her new book its title, is rife with abuse, corruption, deceit and greed. It’s a departure from her previous books in some senses – the setting for one – but Moshfegh’s characteristically bleak outlook prevails. She excels in creating wholly unlikeable characters, yet still manages to stir in the reader a feeling of empathy, even if it is rooted more in pity than affection. The book follows a host of characters of differing wealth and social status, in a tense and desperate struggle for power and survival. Marek, born with physical disabilities, is berated and abused by his father, Jude, who himself feels alone and rejected, an outcast from the rest of the village. Ina, hardened by a life of fending for herself, is wet nurse to several generations of Lapvonians, a duty she carries out with cool detachment and Villiam, the lord of Lapvona is petty and easily bored, playing god from his manor on top of the hill.

I listened to an interview with Moshfegh a while ago where she spoke about switching to writing in the third person for Lapvona, where previously, for books such as My Year of Rest and Relaxation and Death in Her Hands, she’s always written in the first. She said it allowed her to feel both close to her characters, but also more able to be surprised by them, which I was thinking about a lot while reading. Through each character I felt I got a full scope of this strange and magical place and I found myself totally immersed in the world as seen through their eyes. There’s some really gruesome bits, such as when the villagers are subjected to a punishing drought and start to turn on each other in darkly terrifying ways. But, amongst all the suffering there is a kind of sinister comedy in the eccentricity of Moshfegh’s characters, their self-obsession and their disdain for one another. In the same interview she said “I kind of see myself as part comedian, and comedy is about the horror of humanity.”