~*~*~*~*~*what delia read recently~*~*~*~*~

Tell Me I’m An Artist by Chelsea Martin

Going to college in 2011 is a rare experience, a whole other world. I never thought I’d see that world again. It feels like an alien dream of getting too high at a house party or writing an essay about Paradise Lost or standing around a long table full of my classmate’s screen-prints and explaining how I felt about each image. Fumbling along the edges of this coming-of-age time, there’s also the realization of superficial friendships, and the strange dichotomy of identity – while we were away at school, accruing debt, there’s still the family we left at home, our past.

I love Chelsea Martin’s memoir “Caca Dolce” – it sits on my bookshelf, one of my favorites for funny and honest writing about living in the world. “Tell Me I’m An Artist” is Martin’s first novel, and I listened to it as an audiobook. Luckily the audiobook reader had a sarcastic voice to match. Not even halfway through the book, I had to text my three best friends that they needed to read it, too.

The premise of “Tell Me I’m An Artist” seems goofy as hell – a college student at a San Francisco art school spends a semester procrastinating on a final project for a film class, a “self-portrait”, which she will do by recreating Wes Anderson’s Rushmore, a movie she has never seen. There are lots of cultural references of the time (flaming hot Cheetos, “F*ck You” by CeeLo Green) and awkward mundane moments of interacting with new college friends, but also a ton of introspection that made this book feel so real to me.

The most realistic thing about the book is its depiction of class differences between Joey, the main character, and her best friend Suz, who has wealthy artist parents. Joey comes from a working-class background with a single mom, and her mom keeps calling her to tell her her sister is missing: her sister who is a drug addict, whose boyfriend works at GameStop, and whose baby is left in the mom’s hands, even though she can’t afford childcare. Throughout the book, Joey walks into a different room to take phone calls from her mom about the crisis with the sister, and then afterwards slips back into her “art student” life. The two lives don’t touch, and Suz never knows what Joey is going through. Joey agrees to go to a ramen restaurant with Suz and gets a rude awakening that she can’t afford it: it’s not the 99 cent packet kind. This kind of harshness appears as extremely funny in Martin’s writing, and also frustratingly sad.

My favorite realization through Joey’s point-of-view: at some point, everyone discusses the autobiographical elements of the singular films during class critique, but no one acknowledges the juxtaposition of the vastly different lives.

Frank: sonnets by Diane Seuss

“Frank: sonnets” by Diane Seuss had been on my to-read list for a while, and I love the cover with the seemingly candid photo of a shirtless friend. It’s a book of poems only in sonnet form, 14 lines. Even if these lines are really long, taking up the length of paper so that it needs to be folded up. I’m not sure if the poems stuck to iambic pentameter or anything, but I wouldn’t be surprised either way. Seuss is a rebel, taking the ancient formula and injecting it with real-life bullshit, real talk, and longing. There are main characters and stories here that are autobiographical: a childhood of wanting to get saved by the church, then the drug addicted boyfriend, a vibrant friend who ended up passing away from AIDS, and a son who became addicted and almost died, too. She is in real dialogue with these people, and one sonnet is even written by her son in full. I often look to poetry for wisdom, or to eavesdrop. In “Frank” I found the conversations I desire: about music and art, life and death.

“how do I explain / this restless search for beauty or relief?”

“I remember begging to die when I gave / birth and begging to be born when I was dying.”

The Hero of This Book by Elizabeth McCracken

Elizabeth McCracken reads “The Hero of This Book” in her own voice for the audiobook version, and thank god. It feels so clear to hear the cranky bits, the familial knowing, in her clever way of speaking, full-bodied in her lower-toned rhythm. I had been borrowing my boyfriend’s airpods to listen to this, even though I am a staunch believer in over-the-ear headphones. This feels right. It’s a book of contradictions. McCracken’s narrator tells us constantly that the book we are reading is not a memoir, yet she instructs us how to make up details about a hotel clerk in order to make a real story into a fictional one.

Here’s the story: an American narrator wanders around London as a tourist, getting on the London Eye, seeing a Shakespeare play, all the while thinking of her mother, who has recently died. London was the last place they had traveled together, and the city doubles with these memories. Most of the book becomes a 3D model rendering of “the hero of the book”, the mother. The mother’s quirks and appearance are described in heavy detail – a tiny Jewish disabled woman, who only wears hard-to-put-on Keds, with long black hair, with a hoarding problem, and a lust-for-life that McCracken accurately distributes. In this type of writing comes the question: do children really know their parents? Is it a daughter’s (writer’s) duty to remember them, and share them?

The narrator reminds us over and over again: the mother didn’t ever want her writer daughter to write about her, especially in a sentimental way. Yet the book exists, after the mother has died, to do this such thing. The grief document holds onto someone whose liveliness makes it hard to realize she has fully vanished. At first it annoyed me that “The Hero of This Book” is written as fiction instead of memoir, as if it isn’t being fully honest with itself. This is a clear portrait of Elizabeth McCracken’s mother (and father), truly! But then I thought about fulfilling the wishes of our dead loved ones, how their privacy can be kept with certain rearranging and labels, and also our own.

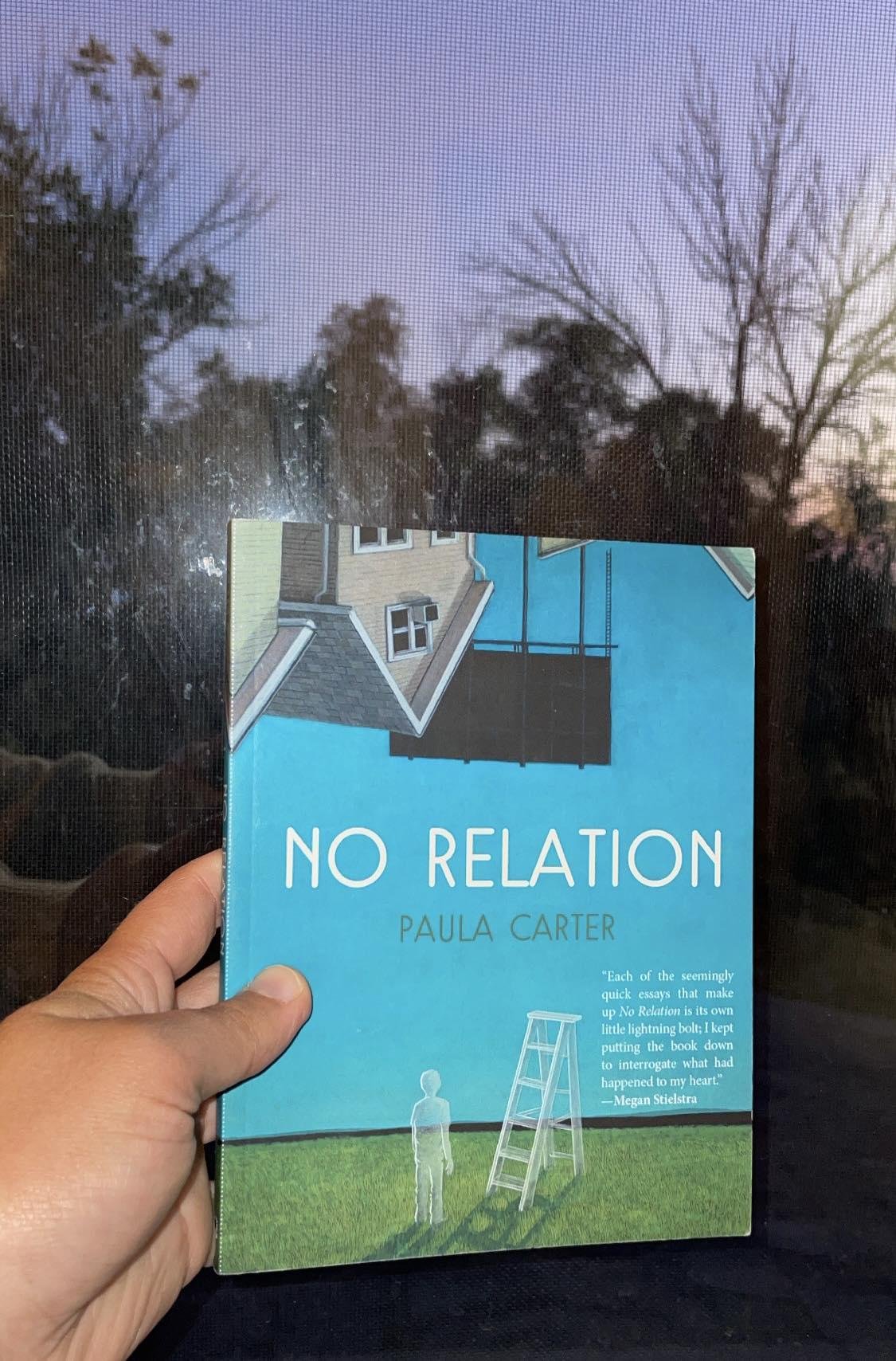

No Relation by Paula Carter

“No Relation” is a fragmented nonfiction book that I got from Black Lawrence Press. Paula Carter’s storytelling style turns to snapshot sensory scenes and brief yet bold questioning. What does it mean to be close to a boyfriend’s two young sons? She creates these little chapters to tell the story of dating a man with kids, and then what happened after breaking up, when her love for the boys had nowhere to land. Each chapter feels drafty like windows, leading into different elements of how relationships evolve: close, closer, further, far. She experiments: inside the fairytale of the stepmother who turns her stepson into soup, there are footnotes about cooking with the boys, remembering what they liked and didn’t like. Carter is a woman in her 30s, childless, but at one point, children roamed her rooms. Like any memoir, I get the sense that a key element for why it was written was to prove that it was real, and not all just a dream.