WORMS DIGEST

Arcadia Molinas

Hello from Malaysia Worms!! I’m in Southeast Asia for a couple of weeks and of course, I’ve brought (and bought) a couple of books with me.

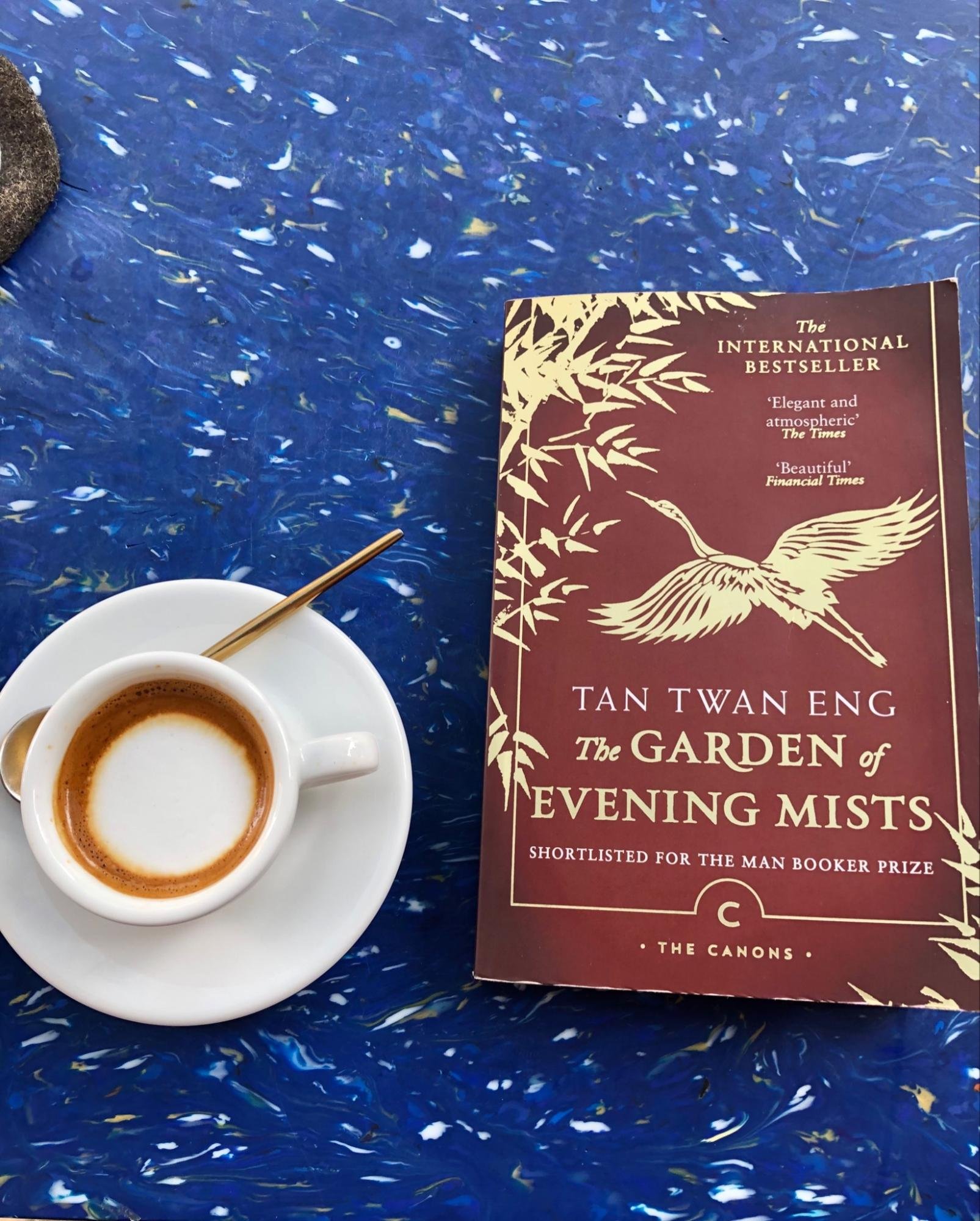

The Garden of Evening Mists by Tan Twan Eng

What is gardening but the controlling and perfecting of nature?

I picked this up in a massive, massive bookshop in Kuala Lumpur for the first leg of my trip. This was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize and I’m having a great time with it so far. It’s the perfect mix of history and fiction, providing me with a crash course on the nuances of Malaysian conflicts, identities and past as well as aweing me with the tender descriptions of the tropical landscape.

The plot is rich and touches upon many different subjects. Briefly, the book tells the story of Yun Ling, who was a POW during the Japanese occupation of Malaya in the second World War. After her imprisonment, she vows to build a Japanese garden for her sister, who died at the hands of the invaders and who really loved the serene and all encompassing philosophy behind the gardens. Enter Aritomo, once the Emperor of Japan’s gardener, now a retired gardener living in the mountains of Malaya. Their meeting reveals the intricacies of relations between peoples in Southeast Asia, as well as the intricacies of attempting to control nature to fit different visions.

Tan Twan Eng’s writing dazzles, providing moments of acute insight and painting pictures of the landscape that are magical, mystical and spring alive off the page.

It is hard to describe what entering a rainforest is like. Conditioned to the recognisable lines and shapes one sees every day in towns and villages, the eye is overwhelmed by the limitless varieties of saplings, shrubs, trees, ferns and grass, all exploding into life without any apparent sense of order or restraint. The world appears uniform in colour, almost monochromatic. Then, gradually, one begins to take in the gradations of green: emerald, khaki, celadon, lime, chartreuse, avocado, olive. As the eye recalibrates itself, other colours begin to emerge, pushing out to claim their place: tree trunks streaked with white; yellow liverworts and red sundew in shafts of sunlight; the pink flowers of a twisting climber garland around a tree trunk.

Our Wives Under the Sea by Julia Armfield

I started this on the plane journey here, and haven't read much of it yet, but so far it’s looking promising. After Leah goes on a submarine expedition that mysteriously loses communication with dry land, she will return to her wife Miri a woman changed. So far the prose weaves heavily charged symbols between the two protagonists and evokes visceral reactions from the readers. Leah, adjusting to life back on the surface, surfers underwater flashbacks as her skin swells with blood from the change in pressure or she craves the sound of water whooshing down a drain.

Excited to see where this goes.

Gay Bar: Why We Went Out by Jeremy Atherton

I picked this up in London just before leaving because I was interested in writing about going out, dancing, clubbing and also there was a quote by Maggie Nelson on the front cover so say no more. Like Our Wives, I’ve read the first couple of chapters and what most appeals to me so far is the references Jeremy Atherton Lin layers onto his experiences of going out to gay bars. From Walt Whitman to Derrida to Michelle Tea, the text is incredibly enriched by these different lens and perspectives. Keeping a pen close by at all times when reading to scribble around the margins and highlight particularly insightful parts.

Emily

I saw this movie about Emily Brontë’s life starring Emma McKay on the plane journey and found myself tearing up near the end. Biopics on famous authors are (obviously) an easy go-to for me. Emily Brontë’s the ‘weird’ sister, constantly living in a world of her own make and preferring the company of her reckless brother, drinking and consuming opium to trying to follow a more conventional path like her sisters, who venture out and become teachers, integrating themselves thus in society. I liked seeing a representation of a woman inclined to hedonism (if it can be called that) and mischievousness. There was something viscerally alive in McKay’s representation of Emily and my heart raced at my viewing.

I also read this review of the show ‘A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography’ by trusty Worm Jess Cole. I managed to catch the show just before leaving as part of my Compost Artist Date <3 and I loved it!!!!

PIERCE ELDRIDGE

a rock a river a street by Steffani Jemison is an expansive read that flows quite naturally through our unnamed narrators engagement with things, from her body’s temporality toward the objectification of it, in relationship with other things around her, such as: murals, statues, and pristine grocery store layouts; we even see the comparison in people, new friendships made, how meeting, touching and engaging with another can create such interesting tensions of selfhood in moments of sharing. It's a bodily exploration, where gestures and the physicality of our main character speak directly to racial identity politics, how hypervigilant and tenuous it can be to live in parallel to an existence afforded sanctuary with one deemed meak. Our narrator holds in her voice for what feels like her whole lifetime until her shins give in from all the running she does, from all the built up opinions and gold inside of her all just giving way. She’s regularly forgotten or confused with another person, and in a way the book reads as the navigation of someone trying to peel themselves over everything, camouflaging and resting across foreign surfaces, until they become deeply uncomfortable with the reality of being subservient in their new territory having lost their sense of self in the process of splaying. One of my favourite parts resembles this thought, attached here: And what I realised is that I had dodged a bullet—that if she hadn’t dissolved into them, I would have dissolved into her, and then who would I be? No, groups were not for me.

Open Throat by Henry Hoke is really beautiful. I actually managed to read it in one sitting, which I hadn’t expected to do, but the way the structure caused a percussive movement from line to line was really absorbing. In hindsight, it's really depressing to think about a queer mountain lion being ostracised in a burning world, no less under the grotesque backdrop of vanity in the Hollywood hills. I think I agree with one of the comments on Goodreads that says it’s less about the mountain lion being queer—there is one moment the mountain lion spies a gay couple nutting in each other and is aroused—but more a commentary on the transgressions of queerness; which broadens its placement, to me at least. I actually read it as a ‘trans’ story, this mountain lion terrifying by the perception of humans, juxtaposed by an internal world that longs to be felt. I particularly loved the part in the novel where our mountain lion is on a couch—invited into the home of ‘little slaughter’ (LS), the name of a young child—licking and flicking their paws to be viewed as docile; very ‘rawwr’ but make it cute, not a threat, but please just leave me be. It also felt very T4T when LS said to our mountain lion that they’ve been summoning them to the abode, calling to a higher power for an almost mythic and destructive kind of love to terrorise her world and the world around her with. Her name, little slaughter, kinda says it all. Little sissy anarchist.

I love that the mountain lion has the last laugh in the end, but cried a lot when reading reflections from our mountain lion that says: every person sitting and walking has hands too and I see all their hands and I know what their hands can do and what their hands would do and the violence waiting behind every motion. There’s a lot in here, ecological devastation, housing crisis, tech and human violence, class disparity, and so forth. It’s one of those greats, already, that could be read a million different ways by its reader. Really powerful, truly loved this one. I’m going to read from this in an upcoming video on the Wormhole for our Picador partnership, stay tuned.

Asteroid City by Wes Anderson genuinely gave me goosebumps at the very end when I knew the movie was summarising itself in that classic bookend style Anderson is so known for. In a very different way to his previous films, I felt myself longing for it to continue or for things to get better, yet realised later (in hindsight) that this was the thing—the feeling—Anderson was antagonising me and my emotions to long for most: a feeling of needing resolution in the esoteric nature of the story, which never (at least to me) arrived.

I’m going to make some pretty large claims, so stay with me or leave it as you please, here goes: It’s the ‘cutest’ we’ve ever seen the Anderson aesthetic and I don’t mean to idolise this here, but I think it’s used to punctuate how morbidly alone and silent the film is. It takes on the same type of whimsy as all his other films, but the whimsy starts to feel a little satire, which makes me think that Anderson is expressing a certain type of contempt for what the viewer has come to expect of him. Yet, instead of letting it go entirely, it’s manoeuvred gently to a greater emphasis of Anderson-esk-esk-esk-ism. I felt Anderson at his saddest, truly alone in the wheelhouse of his ideas… but maybe I’m reading into it too much. I feel like his aesthetic, here brighter, bolder, even cleaner than usual had become a schtick, recognised to me now as a very familiar schtick, and thus deployed as one with a certain sense of uncomfortability. The same type of uncomfortability you feel when you recognise someone’s oeuvre as awkward, fragile, and nervous rather than grandeur and confidently placed. When a gimmick such as his renowned ‘vibe’ is made a device to reflect emptiness upon itself, then again onto the world, the landscape, and the people of Asteroid City, I couldn’t help but hold a mirror up to its creator to question the perfectionism; which I think is a fair thing to do—all things considered—for our main character in the film is a fictional person being written about in real time by a black and white, lonely, and seemingly solemn writer that—at certain points in time—beings to commune with his creations. A universe slipping into another universe, the mystic of craft slipping at the hands of its creator.

My second note is: I’m going to go out on a limb here and say that the film is about loneliness and isolation, and I don’t think I feel that way because I went alone, but I think I feel that way because all of the scenes were really sad. Even the sarcastic and matter of fact tone that’s so dominant in Anderson’s worlds was at an all time razor sharpness. When you were laughing, you were also cringing. Mostly, I feel this way because of the major ‘happening’ in the film which leaves everyone and everything feeling totally helpless; even if, indirectly, they remain ‘quirky’ as Anderson (I think) teases us with (remaining tongue and cheek to avoid the malignant pain of solitude, confusion, and worry). I can’t remember the school teacher’s name, but the scene where she’s telling the kids everything they have ever come to know about the universe is probably, absolutely, actually completely wrong (!) made me feel a little sick in the tummy. I know this to be true but to have it portrayed back to me, as if it’s a fairytale, made the mythic illusion of humanness—our existence in isolation on Earth with all other unknowns zipping around the universe—drop for more than a moment, requiring me to sit in it, to wriggle around in all this unknown, making it a difficult watch and uneasy experience. But, in the nature of not steeping there for too long, Anderson pulled us out with a little song and dance (v-cute tbh) leaving the philosophical and scientific provocations looming all over the mystery of the cosmos; bigger than us, more than we’ll ever know, so what’s it all worth?

Maybe—this is my third point now, connecting to both points above—my lonely reading of the film is because no one really overlaps in the flick. I think it could be argued that the photographer capturing the actor, sleeping together and so forth, made their lives intersect in a ‘special’ or ‘meaningful’ way—we could say the same here about their children linking up—but I kinda think that’s garbage and too easy a reading, and that all of them in their communal silo stayed purposefully stagnated from one another; separated by their separateness, removed always, at a distance, with a underscored characteristic of minimal to no empathy for one another. This is why the kid that requests ‘dares’ from everyone is so evidently searching for others to be involved in his careless tasks. If he were to hurt himself alone, to take risks in isolation, he’d remain as he’d always been: unnoticed, underfelt, and retired to (what I believe to be) suicidal ideation. But his redeeming feature, which is portrayed as irritable and annoying, is his continuous question of ‘do you dare me?’ However irresponsible his asks to the others are, within the question remains an answer, and in the answer—even if he does or doesn’t follow through—his adrenaline spikes and he is unstoppable for he is noticed, if only briefly, by someone other than himself. Ooft. It’s really complex and emotional. Toward the end he’s asked why he needs to be dared all the time and very earnestly he has no answer. His silence emphasises the film’s plot further that the most difficult of emotions we feel have no succinct answers, they cannot be rationalised, however smart we think we are or however carelessly we choose to act when others are engaged and watching.

Fundamentally (continuing point three above), everyone remains apart and it feels like there is no sincere connection made between anyone. As quickly as they arrived with one another, they departed sooner. Maybe this is because ‘care’ feels really unforgiving in the film, the burial of the mother in a tupperware container could be an example of this being ‘cute’ and ‘sentimental’ but I read it as really morbid and harrowing especially as the young girls cast a spell over it. Another example could be when the photographer burns his hand on the girl, the actor from the other room peering in to say, ‘oh you really did it’ without any offer to tend to the damage.

I think with all of this, playing through my mind as I departed the cinema, put into perspective just how distant we are from ever really knowing anything about someone else, about aliens, about other people's intimate emotions, about what brings them to do such crass or beautiful things… we’ll never know. And as we begin to shape the answers we need to hear to keep us going, they become unuseful. We discard our stability because the fondness and likeness of things becomes too cosy or thoughtful, and we move onto and into the things we can’t fathom. Until finally we come to realise, as I feel Anderson has, that we will continue to be faced with questions we cannot answer because of the reality of the truths we cannot swallow.

I think I’m uncomfortably sitting within that at the moment, but something also alleviates me—lessening the burden—in knowing that I’m not the only one trying to know the intimate worlds of everyone else around me whilst excavating myself in the process. I think I just need to make peace with never knowing anything, but then what does that make me?

I will hear the following booming through me for a while, quotes from the film: ‘You can’t wake up if you don’t go to sleep.’ Even more unsettling: ‘It doesn’t matter, just keep telling the story.’

Image of a highway that goes nowhere from Asteroid City.

Image of a cunty worm being fierce.