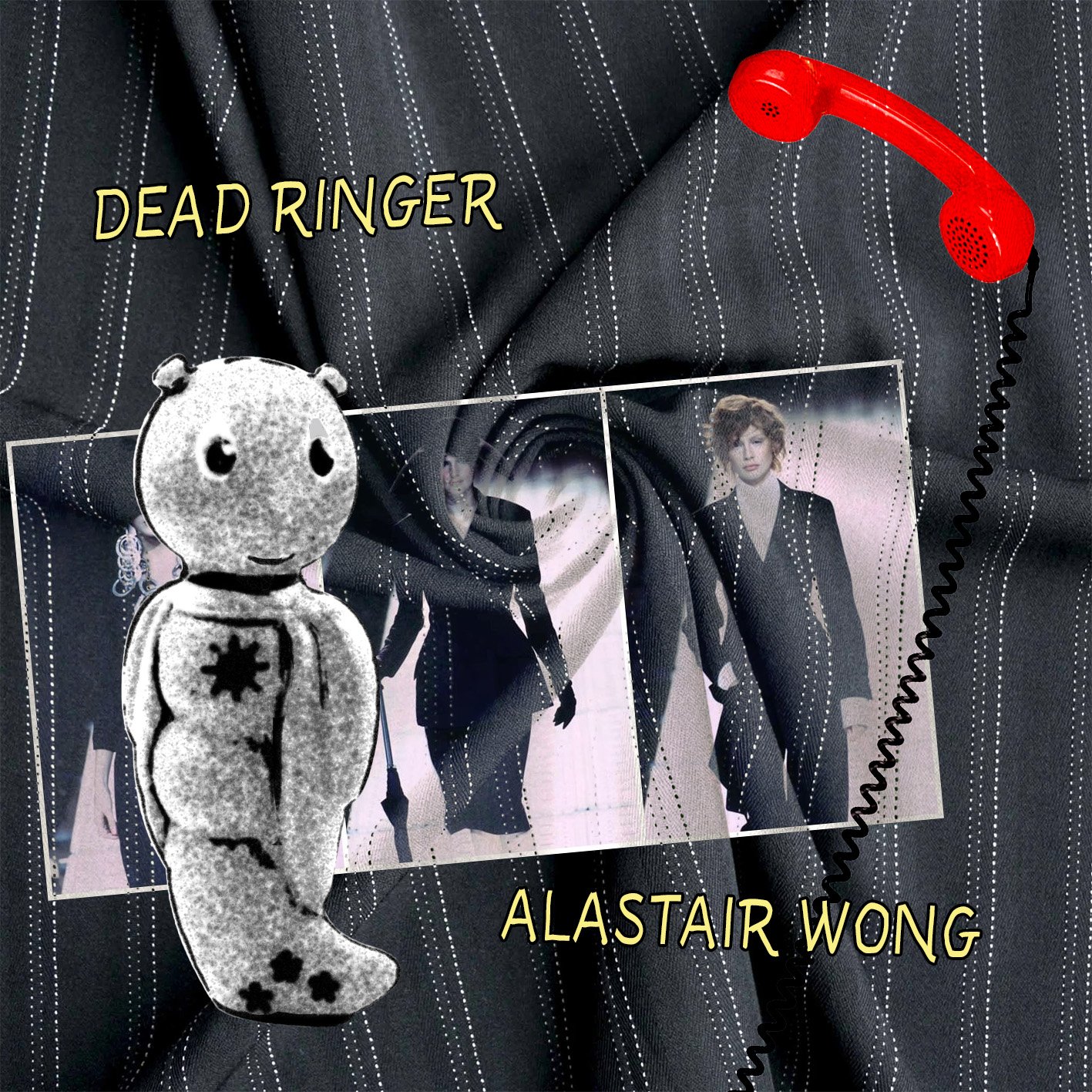

Dead Ringer

by Alastair Wong

She dives. Plume of splash into brown pond, whose surface slips open to swallow her before shutting with a tremble like unset jelly. She swims: see her glide into being with every lazy lingering stroke beneath the bare-branched willows and mistletoes, snow on the ground, fresh fallen snow. It seems magic when she plunges, pauses, then emerges improbably distant, the way pond life flashes in and out of water—a dragonfly over there, did you catch it? Look closely. A shock of platinum hair rising, her many silver earrings glinting like fish scales. Then she’s off again, strong swimmer, hands cupped and buttering through water.

A man is present, young man, easily mistaken for a boy. Idling on the bank with a steady gaze. Thinking: Even in her wetsuit, wouldn’t the water near zero feel scalding? He dunks his hand, endures five seconds before flinching. The hand emerges raw pink. He stands, rubs icy palm against his jeans, the roughness of denim feeling, he isn’t sure why, like safety. Despite her age, or perhaps because of it, she is stronger than him—mentally speaking. More tolerant, at least, to pain. Does the cold hurt her? How is he to know other minds?

She’s far. Perhaps twenty metres. And the further she goes the more he feels neglected. This he is used to. He plays with his hair, parts it weirdly before settling on his usual style. With his heel he grinds down snow, stubbing an imagined cigarette. Warmth.

Again she plunges. This time he counts nearly a minute before she emerges.

Stooping, he finds flat stones, skims them. Considers, momentarily, the intrusive thought saying Aim in her direction, which he doesn’t do; he goes for a record. Five bounces. Now eight. Personal best. He doesn’t want to think What the hell am I doing here, but then he’s thought it already, hasn’t he, and now thinks it incessantly.

Phone buzzes in his jeans—startling him like his deep marrow is what’s rattling. Without checking he knows it’s Papa. Again. Knows the text demands his whereabouts. Maybe, too, a voicemail in Cantonese saying, Son, where are you? Come home. We must talk. Men shouldn’t hide from obligations.

He paces arms crossed behind his back the way his Papa has lately started walking, stoop-shouldered, the caricature of a wizened Chinese. He mocks what he in the lushness of his youth believes is impossible for him to become, to ward off the certainty of his becoming it: becoming like his father. Papa suddenly so old. What would he not do to avoid facing Papa, today or preferably ever, even stand in the snow watching a stranger swimming.

Again she plunges. He counts—sixty seconds, more—keeps counting.

***

Earlier that same morning, they meet on a train northbound from London. The windows are fogged over, making the fast-passing landscapes appear ghostly and the carriage itself claustrophobically narrow. What light gets in has the queer sepia tint of antique photographs. People stare avidly into their phones, tug at collars, cough. He imagines the train shuttling through time, whether forwards or backwards he doesn’t care. Any time but the present.

And doesn’t she seem shot from another era, that woman across the aisle in her crow-black suit. Yohji Yamamoto, judging by the cut—the billowing balloon pants and padded masculine shoulder. No other designer could make a woman look as self-possessed. Older season too, worn-in and slightly pilling and boasting—are those?—real horn buttons. The fabric seems gabardine or broadcloth. He wants to touch the wool. Her shoes are Mary Janes, childish shoes, but finished in patent leather like a pair of glossy cherries. He wants to feel the leather. Her socks are nude and fleshy. He can’t help feeling taken by the sight of her well-made suit. Funny word: taken. But apt given his love of textiles does approach fetish, the erotics of sumptuous cloth.

He scrutinises his reflection in the compact from his purse, then powders his forehead and adjusts his cropped baby tee that says ‘Father Figure’ in Comic Sans, flaunting the abdominals he works via crunches ad nauseam. Thinness, too, obsesses him. And she is gaunt in the way of models, not the sickly. She leafs through a worn book with deckle edges. The black of her clothes is absolute; it says don’t bother me.

Still, he bothers her. Intrudes her space and points at her book. She looks over, surprised at first and frowning, then, suddenly, a turn: becoming bashful as a schoolgirl before their headmaster. Her nose is strong, slightly kinked, and her head is small as a bird’s and looks odd peeking out from a suit so capacious, especially with that mess of boyish hair, peroxide, close-cut. Seeing her wrinkles—some hairline, some deep—he can’t quite hazard how old she is, only that she seems to have lived.

It’s Shakespeare, she says. Twelfth Night. Her voice is unsteady, as though she rarely uses it, but each word lands hard. He imagines pebbles slowly dropping from a palm.

Is it good?

She looks at him stupidly and says, It’s Shakespeare. Then adds, It’s one of the fun ones. All the cross-dressing and disguises. Softening, she smiles.

And soon they are in the dining cart; her idea to buy the young man a tipple to pass the long ride. They fondle plastic cups of red wine, which squeak at barest touch. He picks up the mini bottle, turns it. Thinks to say something like, Good year, this. Compliment the notes of, is that pineapple?

I’m not used to wine so cheap and foul, she says. But options were limited.

He swallows hard and nods like he was just thinking the same thing.

This young man is a graduate in womenswear, on the dole and badly needing a job. At family banquets his Papa will loom and spin the Lazy Susan piled high with steamed fish and Canton roast meats while dismissing him as a tailor. Not a useful job, Papa jokes to the uncles and the aunties. But what can one do, the whims of kids these days. They’re soft. Flowering but not bearing fruit. One of Papa’s endless four-character proverbs designed to spite him. Never does he feel more invisible. He will imagine slamming his chopsticks and shouting he is a dressmaker not a tailor, but how could he ever disrespect Papa by contradicting him so publicly.

Fields blur and pylons sprout. The fogged train cuts shakily up the country.

Already the woman disappoints him. A housewife with no ties to the fashion industry and nothing to offer him except, maybe, money. Yet his fascination persists. Something is hiding beneath the self-assured clothes, which he imagines peeling back. Her gestures betray her cool. See how she hesitates, slops the cup to her mouth, catches a little dribble with her tongue. Her teeth are wine-stained—thin lips—and her free hand scrunches a napkin like she’s in pain. He wants to squeeze her wrist, pet her. Say There, there.

What is she, fifties? Sixties? Calling her beauty withered would be erroneous, it has survived by becoming severer, more essentially animal, hasn’t it? So much history in old skin, he thinks, while staring at the way her cheekbones, her very skull, presses out. He is only twenty-one but has always felt ancient.

More wine? She pours before he responds, spills a drop onto his napkin, blooming red.

It’s not even midday, he says, laughing. What are you, depressed or something?

She throws her head back but doesn’t laugh. She looks at him—the kohl lining her pale green eyes is harshly applied, as by an angry child with a crayon, a protest against beauty standards, perhaps, or orthodoxies of make-up—then says, Yes, maybe just a little. Then laughs hilariously. A laugh he understands to mean its opposite.

She’s lonely, he thinks. He understands lonely, knows how to treat it. He has clients her age who use his body as their balm. She smells of them, in fact: gaudy men’s perfume he knows too well, bottom notes of leather and oud, which now force his memory: big gold watch on a bedside table, his neck choked on a pillow.

He shakes his head, says, What’s with the suit?

This? She examines herself as though confused to discover she owns a body. Belongs to my husband.

And where is the old ball and chain?

She winces. He has hit a nerve. In Japan, she says, what’s left of him sits pretty in an urn. She smiles inscrutably. How about let’s discuss something nice instead? Where is the young man going, what is he doing with his life now he’s graduated from the oh so prestigious Central Saint Martins?

These big questions pang him, and he snaps to, suddenly awake to the speed of the train, the miracle of his being hurtled so decisively forwards in a metal tube, yet feeling fully adrift and aimless. He wants to make dresses, he mumbles, trailing off. He has no real answers. Only Papa has answers.

Papa gave him a year to find a job, at least an internship and, having failed to crack the industry, Papa insists it’s now time to inherit their family fish and chip shop, ‘Her Majesty’s Chippy’, in the sleepy Norfolk town where he whittled away his youth before escaping to study in London. He is ashamed of his humble beginnings, has kept them secret from his London friends, a wealthy and fashionable set who invite him to dinners where he arrives full of lies about having already eaten. He can put it off no longer: he must return to Papa for big talk about his future.

His desperation surprises him as, grabbing her wrist, he says, Take me with you.

***

Her house is a kind of lair: concrete and glass, all open-plan and hard uncomfortable angles, perched and jutting atop a hill. Built to her husband’s spec. What sort of man, he wonders, would choose a design so severe? At the foot of the hill, in the shadow of her home, lies a murky pond.

Shoes off, she says flatly.

It grates him to be reminded this by a white woman. But he does as he is told. Chews his lip and removes his platform crocs. The heavy front door clicks shut. The soundproofing is absolute. Not even the peep of a bird. So used to London’s hubbub, he bristles at the silence. Her voice sounds different now, trembling gone, just hardness remaining. Whatever vulnerability he’d sensed in her now seems imagined.

She keeps her jacket on and slides in socks toward the multi-door fridge-freezer. The thing is gargantuan, the biggest unit he has seen, and dwarfs her. She says, Ice lolly? Then turns with a smurf blue popsicle already wagging from pursed lips.

You what?

I’m hosting, she says, offering you a snack. You’re not above an ice lolly, are you? I’m the one who should be avoiding sugar.

It’s not—I’m not—it’s freezing out. I’m not warm yet.

From outside the white sky presses in flat like an ironed bedsheet. Floor-to-ceiling windows give out onto a large balcony. The vista seems endless: the Stiffkey salt marshes and the North Sea beyond.

They sit on bar stools at the kitchen island, fiddle with their ice lollies. She says, You look, what, like you frequent public pools.

Is that a neg?

A neg…. She seems to search her brain. I’m not used to having people in my space, I suppose. What I meant was you have swimmer’s shoulders. She pinches them as though inspecting meat at a market. This is the first time she has laid hands on him and her touch is frigid and firm.

She leans in and pushes hard on his thigh.

He jerks up. The bar stool clatters.

Sorry, she says, laughing. Sorry, sorry, I’ve given you a fright.

He stares, his eyes dry, not willing to blink just in case—in case what?

You were shaking your leg, she explains. The Japanese have a saying about it, 'bimbo yusuri’. Fidgeting is poor manners all over Asia. You know this, of course.

Dimly, he recalls Papa slapping his calves and muttering in Cantonese that those who quiver are weak-willed and feeble. His having forgotten this proverb seems to confirm the fraudulence he already suspects of himself: that he is a failed Cantonese. Papa would hate this woman simply because he hated the Japanese, who had occupied Kan Tau Wai, their family village in Hong Kong. Japanese soldiers had done something vicious to Gran, that much he had gathered, though whenever he pressed for detail Papa went cold. His family does not unpack history, feelings.

All over Asia? He wants to sneer and ask if she also means Tajikistan or perhaps Bangladesh. Papa would make just such a snide remark, but he is not his Papa, not yet.

She smiles vaguely. Forget it. Just my pet peeve.

Phone buzzes.

Aren’t you going to get that?

He shrugs. They watch the phone judder across the marble counter. When the buzzing finally quits, the stillness of the house is deafening.

She breaks the silence, says, Let me tell you about the art. Then waves nonchalantly at blobs on canvases, no doubt requiring advanced degrees to interpret. At hanging kimonos, Edo-period vases. By the way she holds forth about the furnishings—more like a docent than curator—he assumes they were her husband’s. If the Chinese invented porcelain, she says, then the Japanese perfected it. Same goes for silk. Look at these kimonos. Touch them if you like, if you promise to be gentle.

Feeling the plump silk, the extravagant embroidery, his heart tingles, and it takes something from him to feign uninterest to this woman so patronising. He moves, instead, to a mahogany cabinet. Flicks it open without permission. And in his periphery she flinches as though he has swiped at her wildly. The cabinet is really a shrine, a butsudan with folding doors and a pagoda roof. A bowl of rice with a plastic shine and a packet of Hi-Lite cigarettes, still in glossy cellophane, lie neatly before a photo of the stern dead husband.

At home, the home he can’t bear returning to, there’s a shrine like this too. Papa maintains it meticulously for Gran, done up in the Chinese style of red and gold, with offerings of rice wine and tea and tangerines—Gran’s favourite. Papa will stand before this shrine, dead-eyed and mumbling, burning incense and joss paper without end.

She is staring. Maybe I’m not supposed to say this. She hesitates. But you look like him, you know, when he was young I mean.

He lifts the frame and examines the face for his likeness—a flat nose? a certain line of jaw?—and sees none. If anything the husband resembles Papa, but barely. Somehow the photo disappoints. The husband, how nondescript, how nearly anonymous. He glances at her, this alien woman. He can’t imagine the pair fucking.

She sucks her lolly, her tongue gone blue, crunches ice between her bright white teeth. The sound shudders him. She narrows her eyes and says, Fancy a swim?

***

She’s been down too long, he thinks—isn’t sure, has fumbled the count somewhere in his daydreams. When she finally splashes out, her arms are kinked and waving oddly. At this distance he can’t make out her expression. He waves back. Is she?—she seems to be—thrashing.

Again his phone is buzzing. He chucks it behind and dives in. The water, cold and jolting, constricts his chest. His jaw chatters. His sopping jeans are heavy. He focuses on his stroke, the kick and rhythm of his legs. Swims. When he finds her, she’s adrift and tangled in brown weeds, eyes closed. From beneath her armpits he hauls her, goes under himself and gulps water, before finally clambering onto the reed-lined shore.

There she lies, drowned thing, wet hair dragged back, lips blue. The black makeup around her eyes has run amok, dripping like some caricature of a tragic actress. Pond musk rises from her. He feels a pulse, leans in. CPR, should he? Her chest, he now notices, is unnaturally flat; the word that comes to mind is shorn. He fantasises, absurdly, taking her measurements, the intimacy of the act, tape quivering around her body—commands: arms up, now down—imagines making her a dress. What textile? Nothing airy like tulle, only duchesse silk satin, yes, that most disobedient of fabrics, would be proper for a woman so advanced. He has an erection, he realises, one he doesn’t understand or understands only vaguely. He shudders like a wet dog, trying to scramble his brain.

***

He understands fantasy. He sells it. It began when he moved to London and discovered how expensive textiles were. Some clients just wanted conversation. Others, usually men, pressed for more, got off on costume, on dressing him up or down. One liked him in skirts—or ‘kilts’ as the gruff man insisted on calling them. Sportswear, too, was big. Gym shorts whose waistbands had enough give. But the most popular request was having him play a schoolboy: wide slacks, fat little necktie, defiant moue. It suited his baby face.

Women were trickier customers. They made no demands and liked him however he came, bought him lilacs, dark chocolates. Once even a jigsaw puzzle, as though he were some distant nephew they didn’t know what better to do with. Their kindnesses were cloying and worse were their desires, so obscure and complicated. Men had no trouble ordering him to raise his legs, get on his side. Whereas for women, spelling things out meant disenchantment. They wanted him to lead, and he was no leader. But what he found intolerable were the stories these women told that made him want to gum up his ears, those strings of dispassionate former husbands who’d backhanded them so casually, even cracked them in the head with hardback books. Six stitches and a lie in A&E: Doctor, I fell off my bike. Stories of violence quickly became stories of assault. Without exception they all had stories of assault. And, listening, he felt implicated, the masculine part of him did, that inborn masculinity he’d neither claimed nor chosen but for which he was nevertheless, in those intimate, closeted rooms, the only possible surrogate. Even if women tipped more, he preferred men. Their straight shooting. It wasn’t work he necessarily minded. A job is not something to love, as Papa always says.

***

Her eyes have been open for a while. No coughing.

He falls to the side. What the hell was that? he says. His hands go tense gripping fistfuls of dirt.

I had a wee cramp in my foot. Right here. She sits up, takes his muddy hand and traces her arch. He feels along his spine that he is the one being tickled.

She’s deranged, he mutters, absolutely unhinged.

Don’t blame me for—you’re the one overreacting. I was fine, a little out of breath is all.

He stops. Did you pretend to drown, so I’d save you? He’s rattled. If she is capable of this then she is capable of anything.

No one forced you to come here, she says, or asked you to intervene. She tilts her head and squints.

He knows what he saw. He doesn’t believe her. He does, second guesses. What did he see? His heart gallops. He says, I’d like to go home now.

She is pointing and tittering. He follows her finger down to his still-bulging crotch. She throws him a towel, which he scrabbles for and sullies with mud.

Shivering back uphill, he makes certain to follow behind, carefully watching the tiny impressions her shoes make in the snow, her hands clasped innocently behind. He measures her with his eyes, over and over. Reminding himself: he is the man here and nearly a head taller.

***

But she has ways of coaxing him. Doesn’t a hot shower sound nice before you leave?

He goes, but reluctantly, stinking of pond and trailing droplets over the concrete floors that make him feel like a stain. He hears a rumble then, feels vibrations through his toes, pauses, turns. Says, What’s that?

What’s, oh…the underfloor heating does that sometimes. Don’t worry. Just the boiler acting up. Makes the floor quake.

Her rain shower’s many knobs confuse him, the water temperature never just so. With her sea sponge and soaps that smell of cedar and oak, he scrubs himself pink. This is how stray dogs feel getting sprayed for lice, he is sure. Why he then squirts her toiletries at random onto the floor he cannot say, only that he feels this puerile need to waste what’s hers and continue leaving his mark.

The shower adjoins a walk-in wardrobe. He hesitates but can’t resist peeping. She has predicted this because inside he finds silk boxers and cashmere socks neatly folded, as well as a note in ornate cursive saying, Pick a suit.

Suits and dresses hang mummified in clear vinyl body bags, which static his hands, jolt his veins. He interprets these shocks as warning. Still, he gropes his hands inside and lingers over cupro and duchesse satin and what he suspects is Vicuña camel or perhaps just very fine cashmere. Maxi gowns with hundreds of hours of handsewn beadwork hang dusty and unpeopled, one-of-one couture tags drooping from the necklines. It angers him, this tomb. Because clothes want bodies, to be in motion, at least on mannequins in museums and not rotting in the sticks so far from the human sprawl. Carefully he unzips a garment bag and removes a dress, holds it against his shoulders in the mirror. Maybe. He is pulling it on when his phone buzzes on the ground and, staring, he feels Papa’s disapproval heavy in the room. He looks again to the mirror and his arms slacken and the dress falls and rumples to the ground.

The woman is here. Standing behind him in the mirror, arms crossed, her distaste barely disguised.

What are you doing, she says. Her face is clean of makeup now and her brow wants to crease but can’t—botox, he realises—so instead the crepey skin around her pale eyes is puckering.

He’s naked, feels his nakedness like sin as he rolls onto the balls of his feet in fight-or-flight preparation for he doesn’t know what.

Look at these delicious suits, she says, coming close to drag her hand over one encased in vinyl; the awful squeak pricks his skin. She says, You want to wear a suit.

Is this a question, did she inflect? I’m just fooling around, he says. This, for me, is research. He squirms under her gaze, the intensity of its loneliness.

Grey ones, she says, ignoring him. Black ones, blue ones—no, blue will never be your colour. Callously she flings the clear and shiny bags and they pile up on the concrete like evidence.

I’d actually like to be alone now, he says. Leave.

She sighs and shuts the door.

It isn’t that she scares him, exactly, but he dreads the urgent, unspoken thing she wants, even as he feels perversely compelled to puzzle it—whatever it is—out. Were it sex that would be graspable, but it seems to be something darker and more clutching. What is certain is her desire winding him tight and clinging like cellophane. Is he breathing, remembering to breathe?

Slumped on the ground, he prods through suits in desultory fashion. Picks one to try on. Though the suit is not his style—double-breasted with fat peak lapels, six horn buttons, real horn again, and double-vented at the back, creases at the elbows from years of diligent wear—it beckons him. And, slipping on the sleeves, his shoulders click in, like bone into socket. A garment tailor-made for another man should not fit him so perfectly, down to the uneven shoulder padding that compensates for slant in the posture, this off-kilter tilt that, unbeknownst to them, everyone possesses. No one is ever parallel. The dust-coloured suit pulls him taut upright and shoulders back, as by a puppet string. He feels broad and powerful.

In the mirror, where there was a boy, he sees, from inside the cockpit of his brain, a man wearing his skin. If Papa could see his son now.

Something itches his neck: in the threadbare lining of the jacket is a stitched label where two names are inscribed; the tailor’s name has faded, leaving only the customer’s: Akiba-Smith Masato.

Striding into the living room, he hears her sharp inhale. And she, prone on the sofa with her legs swanning the air, stares hungrily. He feels thrown, not by her stare, disconcerting as that is, but by the room itself now tingling with a deja-vu enough to make him queasy—the walls and ceiling seem to be nestling inwards, everything bright with strange new intimacy.

There’s another woman in the kitchen, Asian like him. Nearly a granny. That she’s in athleisure would ordinarily repulse him, but a third party, a witness, comes as relief. Her sleeves are bunched high like inflatable armbands as she chops vegetables with a cleaver whose thudding is regular as a metronome. This is Yumi, the woman says. Yumi, say hello.

The woman’s immaculate hands do not speak of work, so Yumi must surely be the help. Still, doesn’t it embarrass her being ordered around like that, kowtowing. Though he understands that in his own way he, too, is under this woman’s cosh.

Yumi offers him a placid grin, then returns to her cleaving. Yumi is preparing us a bite, the woman says.

This is her ploy to make him stay. It won’t work. His wet clothes are in a doggy bag and he will demand she call a car. But he has an urge—rather a compulsion—to revisit the shrine.

There in the vast mirror running along the wall, he catches his reflection again. The man in the mirror insists he stay. He admires his finery. He wavers. This pressure on his shoulders. He considers the photograph of her husband again and nods. Perhaps he was hasty earlier, perhaps a resemblance does exist. He lifts the cigarettes from the shrine, strips their film, and lights one with the zippo he intuits is in his breast pocket. He feels her stare while he tokes and rolls his neck, nearly groaning from pleasure, before ashing on the floor.

How do you feel? she says.

Warm, he says. Dry. His voice sounds unfamiliar to his ear, booming and somehow ugly in a way he is surprised to find himself liking. He says, Ask me something, anything. We hardly know each other.

She considers this, then shakes her head ruefully.

There must be something you want to know.

Nothing, she says, Not even your name. I don’t even want you to speak.

You want me to sit here, a doll. That makes my job easy.

Job? she says, What job?

He shrugs and says, You talk then. Tell me about the dresses. When did you last wear one?

Years, she says. She is tapping her foot slowly. Not since the double mastectomy.

He senses she is withholding. He smokes. They sit quietly in their suits. He ashes on the floor, a gesture to goad her.

She examines her hands, turns them over and, exasperated, says at last, It’s like a betrayal. You wouldn’t understand what it’s like looking down at your wrinkled, bare arms and remembering how proud you once were, remembering all those lost compliments about their slenderness. They’re nothing to show off now. I used to think getting old was something that happened to others.

He can’t imagine her young and plump. But he’d like to see the way her arms look now, the creased skin like well-worn linen. You’ll put on a dress for me. He surprises himself with his demanding. Go on. I’ll choose.

They don’t fit. You want me to look clownish. Her voice is petulant. You want me in a wire bra stuffed full of chicken fillets, is that it? She pulls at her belt loops, flashes her flat stomach, the sharpness of her hip bones like handles on a vase.

He says, Do you have safety pins, a sewing machine?

They compromise: a dress, but with a jacket. A Dior bar suit from 2012 modelled after Monsieur Dior’s New Look introduced in 1947, a period for which the young man holds an aching reverence. He takes in the bust on a cream-coloured silk jacket, chosen because its soft shoulders and cinched waist, structured hips and peplum, are the diametric opposite of the woman’s quotidian armour. The dress beneath has a skirt whose absurd volume and dense knife pleats require some twenty yards of fabric, all held up by a petticoat whose feather boning and layers of stiffened horsehair do the work of Atlas. Such voluptuous excess, considered obscene by some contemporaries, was a reaction to the sober fashions during the German occupation of Paris, still fresh in the memory, and the ongoing rationing of textiles. Women like her in their New Looks—dubbed flower women—could be found flaunting through Paris even as Gran carried Papa on her back in Hong Kong, living in a clay hut and tilling fields in a thin moth-ravaged shirt.

The machine ticks madly as he sews. As he imagines not just sitting but belonging alongside this woman in clothes he has, if not made, at least altered—touched. He pushes aside thoughts of Papa, but Papa is with him always, and never more so than while working on yet another of what Papa would call his frocks.

The original look was styled with a straw-woven rice paddy hat, which he now forces the woman to wear despite her protests of cultural appropriation. But it is absolutely necessary. It makes the silhouette whole. If men wear clothes, women are adorned.

Outside, the salt marshes are lost in night, windows giving out onto a density of stars never seen from London. In her new clothes her edges soften, her hardness seems to melt. And she blushes, a flower woman, twirling for him in her ensemble. They sit opposite each other for dinner, candles lit.

Yumi has made orange chicken and stir-fried Chinese broccoli. He has never had orange chicken in his life. Does the woman believe bastardised Chinese food will make him feel at home, disarm him?

Yumi sits beside him. And he is glad to see Yumi at the table, not squirrelled away in servants’ quarters. When she tries to serve his portion and pour his wine, after an awkward tussle, he manages to stop her and serve everybody himself. He doesn’t want to be waited on, not by Yumi. The woman looks embarrassed—as though their unsightly struggle is beneath her—and focuses on her chopsticks, handling them neatly in black velvet gloves.

What the hell is Chinese broccoli anyway? he snaps. It’s called Gai Lan. Say Gai Lan.

Off guard, the woman butchers the pronunciation, her mouth unused to the tones. He catches Yumi catching herself smiling as he makes the woman repeat after him, a child stuttering through language: Gai Lan.

And neither is the meal fluent like he’d imagined. Between chopsticks clacking, the silence is weighty and unbearable. Another compulsion takes him then, and he finds himself standing before the Dieter Rams shelves neatly housing LPs—third shelf, top left—there it is, where it’s always been. On the record player he plays Reality in Love by Toshifumi Hinata.

This record was a favourite with us. How did you guess?

He sits and wonders if this is true, if this woman is capable of honesty. Steam and spice rise woozily from the heaped plates before them.

I have a request, she says, beckoning him with a flat smile. Here it comes. He feels again that dread, cellophane tight. But the suit pushes back, this pressure from within. It tells him he is surely strong enough to deny her whatever request.

She grips him by the tie and says, Promise you’ll be open-minded. She guides him down and stretches herself to his ear, whispers girlishly, Feed me.

If he is making a face he doesn’t know what kind. This is new, even for someone like him so used to catering to strange palates.

It’s something he used to do for me. The food doesn’t taste like anything unless someone feeds it to me.

That isn’t it, he says. You’re not being honest.

All day she has been staring at him, but not now. She balls herself up and says, Isn’t it nice sometimes being someone’s pet?

He more crumples than sits beside her. And feels himself yielding, almost outside his control. Were they alone he wouldn’t be self-conscious. He understands better than most that anything between two people is possible in private. But Yumi is here. He does choo-choo train noises, lifts her chopsticks with a shaky hand and drops morsels in a manner approaching slapstick, to signal reluctance even as he complies, believing that mockery will distance himself from the intimacy of the act, an intimacy that feels deeper than mere fucking.

When Gran had broken her hip, Papa spent months blowing on hot congee at her bedside and fed her patiently until the end. Now and then Papa would hold a cloth beneath her chin while she took small sips of water from a strawberry-print straw, her lips so withered. And at the sight of Papa’s tenderness, a man usually so clipped and barking, he remembers feeling the hideousness of his jealousy. He was only a boy. Even now at his family shrine there lies a permanent banquet for his grandmother’s ghost. Feeding is, has always been, part of his culture, the culture he has strived thus far to disown. He teems with regret now, has been measurelessly callous, for he has neither bowed to Gran nor left her incense in years, always creeping past her shrine with lowered gaze.

The woman has her eyes squeezed shut and her mouth slack, as in a dentist’s chair. She has removed the rice paddy hat, her small hand moving from tie to tight on his lapel. Candlelight plays on her face. And he becomes sincere in his feeding, pious even, balancing orange globules of chicken on his chopsticks, wiping her lips where rice has stuck, pausing while she chews with undisguised relish.

Is the chicken too hot, he asks her, can you taste it?

She squeaks happily.

You’re certain? he says.

Keep going.

Say aah.

Stop, she says. Stop talking. Then pokes her face up to his and, with her eyes still shut, pushes her tongue into his mouth. He tastes orange. Her tongue probes tentatively, like somebody exploring a cave. Pickaxe, head torch, bucket, shovel. She says, Shut up, shut up and keep going.

A presence, something, falls heavily onto his shoulders. But when he turns to glance, Yumi looks serene, eating as though across from her were two people simply passing the butter.

He dabs sweat from the woman’s glistening brow. She begins unbuttoning her jacket. First a triangle of skin where the neckline plunges, a little moisture, then the edges of mastectomy scars on her chest, its sheer flatness. What he doesn’t expect are more scars, many more; they hesitate over her arms, little vibrations. The jacket falls next, revealing the décolleté neckline and the dress in full. Then the gloves come off and her arms are finally bare. Her skin is not as he had imagined—true, it is wrinkled, but also flushed with life and though ribboned with scars, or perhaps because of this, lovely. He replaces the bowl, the chopsticks neatly balanced.

Your body, what happened?

The woman is shaking. Abstractedly she says, It doesn’t belong to me. She is trying very hard to avoid looking at one corner of the room. Yumi, still plussed, still eating.

He reaches to touch the woman’s skin. Who slaps his hand away. But it is all too late.

Just then, beneath his feet, as though in protest, the floor rumbles and skirts through his bones. The underfloor heating, he says, The boiler. Say something.

The woman opens her eyes, a pleading look. Shakes her head. He feels around his pockets, retrieves his buzzing phone and, unthinkingly, he answers. Begins to breathlessly panic as he realises where he is—which is where? What is he doing? And should Papa begin shouting, how will he justify himself to the man?

But the line is trembling quiet—he checks: Unknown Caller—crackle of slight static. The woman and Yumi both look at him expectantly. Then a voice he doesn’t know, a man’s voice, says, Moshi, moshi. A voice which, calm as a still pond, agitates him. Makes him feel thrown a mile high where now, inside the hollow of his head, cabin pressure is building, bulging his eyes, throbbing his ears. Hands numb, he pats his face. Coughs. It doesn’t feel right, his face doesn’t.

He turns slowly to the woman and asks what it means: Moshi, moshi.

She won’t look at him anymore.

Yumi is the one to answer and without, as he had presumed, any trace of a Japanese accent. In fact, she speaks the Queen’s English. Just like him. And says, We say it answering the telephone to mean hello. But really it means, I speak, I speak.

He puts the man on speakerphone.

Moshi, moshi?

And the woman, frozen, has her mouth gaped like she might still be peckish, or about to scream.

Alastair Wong was shortlisted for the Penguin Random House Merky Books New Writers’ Prize. He was the Truman Capote Fellow at Brooklyn College for an MFA in Fiction, where he also taught. His writing has appeared or is forthcoming in Dazed, Electric Literature and The Iowa Review, among others.