Schizo-Culture: Book and Object

This essay reflects on experiences of abuse, please approach with sensitivity.

This was going to be a reflection on Semiotext(e)'s volumes on Schizo-Culture: The Event, The Book, co-edited by Sylvère Lotringer and David Morris. The volumes document the event and the later publication of an unprecedented exchange between French and American radical thought. The event took place between the 13th and 16th of November 1975 at Columbia University, organised by Semiotext(e), and the publication came together three years later. They both represented a milestone in anti-psychiatric critical thought but in different ways. Psychoanalysis and, particularly, anti-psychiatric thought were central aspects of both the event and the book. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari's now well-known critiques of Freud and Lacan's familialism had until then reverberated only within the confines of French academia. As Guattari explained during the Q&A at the Schizo-Culture event, schizoanalysis was a rupture with Lacan's description of the subconscious within a capitalist system.

Schizoanalysis, particularly developed by Deleuze and Guattari, takes a materialist approach to psychiatry, responding with profound criticism to the dominant discourses of psychoanalysis at the time which, they saw, were embedded in the material conditions of imperialism, capitalism, and the police state. Desire, then, was aimed to be freed from the systems that redeploy it in service of capitalism.

The titular 1975 event, “Schizo-Culture,” came together after Lotringer, at the time working at Columbia University, hosted a series of talks with his French friend Félix Guattari. The event brought together thinkers who had not previously been in contact, such as French philosophers Jean-François Lyotard, Michel Foucault, and Gilles Deleuze, with American thinkers such as William Burroughs, Ti-Grace Atkinson, and John Cage.

Schizo-Culture incorporates these critiques of familialism and the psychiatric institution, but also practices ways in which academic thought could leave an echo chamber and be translated into publication experiments; as Lotringer compiles in the 2014 edition of the “book” and the “event.”

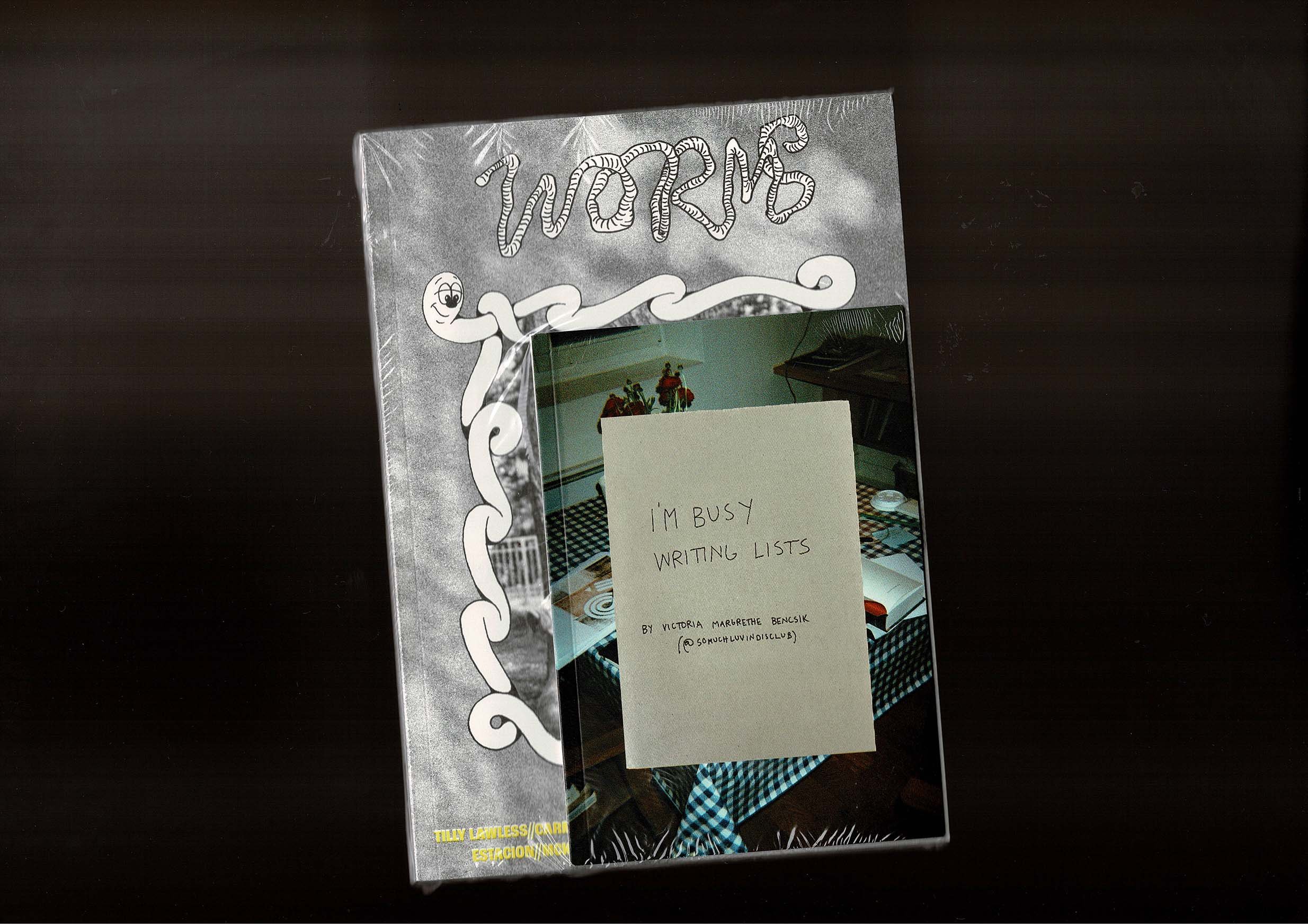

Courtesy of: Semiotext(e)

The book, produced three years later with contributions from John Giorno, Kathy Acker, and Lee Breuer, confirmed this encounter as a break with theory exclusive to academia. This book cemented the event’s break with the exclusive theorising of academia, and filtering into the art scene, but also contributed to the ubiquitous art jargon that still persists today. The volumes, republished four decades later, are full of semi-mythical anecdotes such as Foucault declaring that Columbia was the worst audience, Guattari dissolving an assembly, and other anecdotal displays of intellectual power.

For anyone adjacent to Western art schools, my first sentence might already be loaded with virtue signifiers of cool (Deleuze & Guattari, Semiotext(e), and so on). The first boy I ever loved—and my abuser—showed me this book. He claimed references like D&G as his own, never recognising them as shared discoveries from our many late-night debates. This experience isn’t unique.

If you have had the opportunity to attend a European art school—a trope of ironic, soft-mannered boys would carry these references as a secret and a warning.

The awe is not unjustified; Semiotext(e), as a publisher, took theory outside of academia's self-referential spaces into wider aspects of art, literature, and everyday life to broaden their understanding of popular culture. Semiotext(e) has been run by Sylvère Lotringer, Chris Kraus, and Hedi El Kholti. As Kraus explained, "The texts [...] are less important than the mesh effect they produce together [...] it’s more like an atmosphere of meaning than any particular meaning." I know that writing an article about Schizo-Culture is a personal revenge, a way to reaffirm that intellectual references are not property to anyone in particular.

But life moves faster than plans of vengeance through writing.

Three weeks ago, he died. Now, I have no reason to pretend that these books represent me any more than they represent my abuser or the equally tiresome D&G sadboys fans who defended American Football as the last true emo band and heralded William Burroughs without real passion, only instruction.

Schizo-Culture was my first contact with a thought critically aware of the limits of psychoanalysis. This, to clarify, attracted me even before having read Freud, Lacan, and Jung. To this date, I have no sort of expertise in psychoanalytic studies.

However, Schizo-Culture introduced me, through European writers, to the historical debts owed by bourgeois cis white academics to racialised and queer people.

But not in the expected ways of reading text and it being transferred into knowledge, but more through looking and searching what these thinkers got up to after their big conferences and why they had become desirable for a particular kind of boy who mobilised intellectual power to emotionally dominate their lovers.

As David Morris expresses at the end of one of the Schizo-Culture volumes: "So as it turned out, Schizo-Culture was more about confrontation than connection." Irene Javors, mental health counsellor, writer, and poet who participated in the event, tells Morris that most of the real work of the conference happened away from the "organised chaos and overblown male egos competing with each other." This work took place in workshops run by people directly involved in the problems discussed, such as: "Psychiatry and Social Control," "Schizo-City," "Cinema: Representation and Energetics," "Feminism and Therapy," "Mental Patients' Liberation," "Gay Liberation," and "Politics of Psycho-Surgery."

When I asked this person to leave my life, he took (stole) significant objects of mine with him. Between objects such as my passport, Schizo-Culture volumes made it to the select list. What was in that book, for him to equate it to an identity document? At this point I was growing tired of the intellectual power displayed in the Schizo-Culture Event and its memorabilia that boys these days were reproducing. Seeing this, my close friend Álvaro and I moved flats, got new books, and embarked on a—this time shared—reading of Preciado. If Foucault had introduced his work on The History of Sexuality at Columbia in 1975, Preciado continued to develop how to take the technologies available to us and repurpose them outside the sex/gender structures that serve capital. But the hard truth is that the scenes of power displayed at Schizo-Culture events and the Gucci commercial featuring Preciado (from which I have not yet recovered) do not offer an image of a less egotistical display of intellect. If Schizo-Culture has a particular place in the olympus of the cultural logic taking politicised publishing into the terrain of commodity fetishising presses, events, conferences, or thinkers–then why brush it aside? Why not reflect on Schizo-Culture volumes just as the object? Eventually, it is the object that can be heralded, shown, stolen and mourned.

Courtesy of: Semiotext(e)

If the work at hand took place away from the conferences that named the book, what am I tracing here? It would have been easier – I understand – to take distance and intellectualise the cultural relevance of Schizo-Culture volumes. But what has proven difficult – and the task I have given myself since his death – is to confront a renarration of this book as an object.

However, in the face of the heartbreak of loss, the fear to love, the personal and collective trauma, an intellectualised discussion on this book would be deflecting what is at hand. Journals like Parapraxis or discussions in podcasts like Ordinary Unhappiness start from the recognition of how violence can destroy language because of its untellable effect – but always ensuring to not depoliticise its analysis in the process.

Courtesy of: Semiotext(e)

If my failed literary review is met with a tinge of disappointment at the property relations that the aforementioned thinkers did exercise with their output – what is left to say about the property relations that the book as object reflects about my own experience?

The reference was his, but the book as an object was mine, and he stole it. Writing about it initially meant a way to reaffirm that I also took part in that space of cultural references and it was not something shown to me and stolen from me, a way to interrupt that unchosen passivity. However this is again property relations –

who owns the love story, who owns the reference?

***

You are eighteen, nineteen, you walk and wander with your then-flame, you open the door to your references, your heart, your home. Then, he becomes your abuser. After managing to get him out of your home you check your pile of books and that one in particular is missing, he has stolen it, it is not only a personal vengeance but an intellectual diversion: the object might have been yours but the reference was mine.

It is not only the book that is stolen but my relationship to it. Because I do not want to conflate heartbreak with being an abuse victim, suddenly I am not allowed to tell myself my tale of love. But a big, glutinous silence eats away the potential of discourse, recreation and joy left in reminiscing a then-romance or a book reading.

And then the reiteration begins. The book; the romance, and the heartbreak become an object of repetitive narration – through it, it becomes real and enjoyed. But trauma is exceptional because of its untellable quality, its inability to be narrated. So what is to be told when the romance, the breakup can not be owned because now it forms part of another bigger, unchosen sphere of abuse. When the book in itself has been stolen.

***

Psychoanalyst Avgi Saketopoulou proposes in her book Sexuality Beyond Consent–shown to me by my dear friend Álvaro–there being no return to a pre-traumatic state for traumatised subjects, and therefore psychoanalysis could focus less on healing trauma and become more curious about what can be done with trauma. This change of approach from ‘traumatophobia’ into ‘traumatophilia’, Saketopoulou proposes, can go beyond fetishistic repetition but repetition that can lead to psychic transformation.

So as Saketepoulou questions, what can be done with it? Probably abandon my craving for property relations to the book, to this love story. I don't own it and whether that realisation is the result of trauma or not, I will work with it. The shift from vengeance to grief is still de-narrativizing though. That re-appropriation was still a reiteration, a reference to an original narration: what the book as object can signify; what my experience means.

That literary vengeance was no less an appropriation of the object: the book and therefore me after that experience, I guess. But when speed dialled into solitary grief, what is left to narrate? No one left in this city knew me or him back then. The pandemic, Brexit and general life events washed every witness away from this city. After these past three weeks, I think that is why I brought up Schizo-Culture in the first place: the book laying in my bedroom has always stood as the last witness in this city to the impotence of my narration.

When I move beyond the property of references and experiences, and truly navigate the joints between the ineffable and its recurring re-discovery, I get to where I am, discarding a literary review and allowing a literary description of Schizo-culture both as an object of anxiety and desire. With the blind will of folding and shaping the viscous texture of the unspeakable and exceptional fragmentations that trauma leaves.

Elvira García is a writer and researcher based in London. Her areas of interest focus on visual and material culture and histories of extraction.